Finding Your Roots

Love & Basketball

Season 12 Episode 5 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

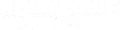

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of basketball stars Brittney Griner and Chris Paul.

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the roots of basketball superstars Brittney Griner and Chris Paul—revealing that they are not the first extraordinary people in their family trees. Telling stories that stretch deep into the past, Gates introduces his guests to relatives who showed courage, talent and grit—connecting Brittney and Chris to their ancestors in ways that they never imagined possible.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Corporate support for Season 11 of FINDING YOUR ROOTS WITH HENRY LOUIS GATES, JR. is provided by Gilead Sciences, Inc., Ancestry® and Johnson & Johnson. Major support is provided by...

Finding Your Roots

Love & Basketball

Season 12 Episode 5 | 52m 9sVideo has Closed Captions

Henry Louis Gates, Jr. explores the roots of basketball superstars Brittney Griner and Chris Paul—revealing that they are not the first extraordinary people in their family trees. Telling stories that stretch deep into the past, Gates introduces his guests to relatives who showed courage, talent and grit—connecting Brittney and Chris to their ancestors in ways that they never imagined possible.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Finding Your Roots

Finding Your Roots is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Explore More Finding Your Roots

A new season of Finding Your Roots is premiering January 7th! Stream now past episodes and tune in to PBS on Tuesdays at 8/7 for all-new episodes as renowned scholar Dr. Henry Louis Gates, Jr. guides influential guests into their roots, uncovering deep secrets, hidden identities and lost ancestors.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipGATES: I'm Henry Louis Gates, Jr.

Welcome to "Finding Your Roots."

In this episode, we'll meet basketball superstars Chris Paul and Brittney Griner.

Two people born to play a game.

GRINER: I was in volleyball practice, and they were like, "Hey, go dunk this."

And I was like, "Okay."

So, I just ran with the ball and just dunked it.

(laughs).

Literally, the next day, the coach came and was like, "You, you come on over here to basketball hall when you get done today."

PAUL: I'm just crazy competitive.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, I don't care what it is.

So, if we playing checkers, if we playing chess, if we playing cards or whatnot... GATES: What if you're playing with a 6-year-old child?

PAUL: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Are you still ruthless?

PAUL: Absolutely.

GATES: To uncover their roots, we've used every tool available.

Genealogists comb through paper trails, stretching back hundreds of years.

GRINER: That is cool.

GATES: While DNA experts utilize the latest advances in genetic analysis to reveal secrets that have lain hidden for generations.

PAUL: My palms are sweating over here.

GATES: And we've compiled it all into a "Book of Life," a record of all of our discoveries.

GRINER: It's mind-blowing.

GATES: And a window into the hidden past.

PAUL: If you was to make this into a feature film, you would look at it like, that's not true.

There's no way that that happened.

GRINER: Whew.

GATES: Did you think we'd get back this far, this quickly?

GRINER: Nah, I didn't think it would go like this, honestly, I'm like shook right now.

GATES: Chris and Brittney are both phenomenal athletes.

In this episode, we'll explore what lies behind their greatness, could it be that they were molded in ways they never could have imagined by the lives of their ancestors?

♪ (theme music playing).

♪ ♪ ♪ (book closes).

♪ ♪ GATES: Chris Paul is basketball royalty.

The future Hall of Famer, a 12-time NBA All-Star, is one of the greatest point guards ever to play the game.

Second all-time, both in steals and assists.

His secret practice, practice, practice.

Chris is legendary for his work ethic and for the passion he brings to the court.

Traits that were first nurtured in him by his father.

PAUL: When you're a kid, you take on the likes of your parents.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: And my dad was a huge, huge football and basketball fan.

And as a kid, my dad coached us.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: You know, so now having kids and going to their games and seeing the people that take the time to actually coach them and go to practices and whatnot.

My dad did that for my team, my brother's team.

And it's crazy to think he still found time to go to work.

GATES: Yeah, that's amazing.

PAUL: Unbelievable.

GATES: Yeah.

PAUL: But the, the biggest thing that my, my dad did was when I was in the fifth grade, uh, he had a basketball court built for us at our house.

GATES: Wow.

PAUL: Right?

And when I say that it's not, it wasn't a full court by any means, but there was this hill behind our house, and actually our, our football coach had a cement company.

GATES: Uh-huh.

PAUL: Right, so he came and laid down like pavement, like right down on this hill, and we put two basketball goals, and it was not a full court by any means, but he basically said, if you guys love this and you really want to do it, here it is.

GATES: Chris took his father's words to heart.

By the time he was in high school, he was one of the best basketball players in his home state of North Carolina, and was being recruited by the top colleges in the country.

An accomplishment made even more remarkable by the fact that Chris stands barely six feet tall.

And back then, he was even shorter.

PAUL: I was always the smallest guy on the team.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: You know, and I was the kid that used to like, pray for height.

When I went to bed at night, I was like, "God, please just make me tall, please."

And, uh, it still hasn't happened, but you, you gotta work with what you got.

GATES: When did you first realize that not only that you were good, but that you had a special talent and you could make a career out of basketball?

PAUL: Right, um, even when I went to college, I didn't know I was going to the NBA.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, I hoped.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: But when I got to college, my work ethic went up just a little bit more.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, and now you start to have a little bit of inclination 'cause people can hype you up and say that you're really, really good, but you know.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, they can't hype you up, but so much.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: But as I continued to get better, I started to say, like, man, I might be able to do this for a living.

GATES: Chris, of course, has done much more than just make a living at basketball.

In 2005, after two years of college, he was drafted by the New Orleans Hornets and won rookie of the year.

He's gone on to thrive in a league of much taller men through an unparalleled combination of talent and effort, becoming one of the highest-paid athletes in the world.

And through it all, Chris has never lost his grounding.

He remains intensely grateful to the people and the game that had brought him so much.

PAUL: I've been in the NBA now since I was 20 years old.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, and at 39, um, there's a lot of things that I did and experienced, like when I was a child and coming up, but then when I got into the NBA, there's been a lot of things that have been taken care of for me.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: And so, um, I didn't go through the struggles that my parents went through in trying to, um, get a house.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, and working, uh, that type of job to try to accumulate wealth.

All of this happened for me at 20 years old.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

Do you still feel joy, pleasure in the game?

PAUL: Absolutely.

GATES: Did you ever burn out as a player?

PAUL: No, no, I don't think I ever burnt out as a player, but I'll tell you something wild that happened this summer.

Um, I went into the house, and I told my wife, I just need to go outside and shoot.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, just go outside and shoot.

Because at some point, you almost get programmed to, every time you go to a gym, it's to train.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: And I fell in love with the game as a kid, just in the backyard.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, just playing around with my brother, practicing things and whatnot.

So, I went outside and just shot for 45 minutes.

GATES: Wow.

PAUL: And just dribbled and started to use my imagination, and I won't say I fell outta love with the game... GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: ...ever, you know, but just sometimes, just remind yourself why you love it so much.

GATES: Right, for the pleasure of it.

PAUL: Yes.

GATES: Just like Chris, Brittney Griner is a surefire Hall of Famer, a 10-time WNBA all-star and three-time Olympic gold medalist.

Widely recognized as one of the greatest players in history.

But Brittney's story is fundamentally different from Chris's.

Growing up in Houston, Brittney towered over her peers from a young age and suffered mightily for it.

GRINER: I hit my big growth spurt probably 7th grade until 12th grade, it was just a constant, like uphill climb for me.

Uh, seventh and eighth grade also was big on the bullying.

The, you know, the girls pointing out how I look different than everybody else.

Literally physically coming up to me and touching my chest and saying like, "Look, she has no chest."

Like, "She is a man."

GATES: Mm.

GRINER: Um, just my voice wasn't as, I guess high pitch as everybody else's.

Um, so yeah, got a lot of picking on pointing at, like, just being told how different I am from everybody else.

GATES: I recoiled when you said that, just to have someone touch you.

GRINER: Yeah, it was tough times back then.

GATES: Oh, I'm so sorry you had to go through that.

GRINER: Yeah.

GATES: Ironically, Brittney's height would provide her salvation.

She started playing basketball in ninth grade when a coach saw her dunking a volleyball on a dare.

Within a year, she was dominating on both offense and defense and attracting attention from college coaches across the country.

GRINER: That's when I really felt like, "Okay, I got this."

Uh, I started getting a lot more, um, scholarships as well, like flooded.

And it wasn't like the, the typical like, "Oh, we're just sending this out to the kids."

Here's like, you know, "You could come to this school."

It was more like, "No, we, we want you to come here."

Like, you could tell it was a little bit more tailored to me, and I was like, "Oh, I, I'm liking this."

This feeling wanted from going from, you know, being bullied before high school and not being the cool kid, and just kind of being on the outside, to now I am the cool kid, I am the athlete, and people want you.

GATES: Brittney Griner, superstar!

(laughter).

Brittney's star has risen higher than anyone ever could have imagined.

She led Baylor University to an undefeated season and a national championship before becoming an icon in the WNBA.

She's also used her talents to impact the world well beyond sports.

A prominent social activist, she's championed women's equality, LGBTQ rights, and, after her infamous imprisonment in Russia, she's been advocating for Americans detained overseas.

But Brittney told me that many of her greatest triumphs have occurred in private, stretching all the way back to when she was a teenager and she came out to her family.

Something our father initially found hard to accept.

GRINER: He didn't want another strike against me.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Already a woman.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Already Black.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Two strikes, now you adding, you are gay too.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Like, he just knew the battle that I would have.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: He wasn't homophobic, he wasn't scared of gay people or hated gay people, it was just, he just didn't want me to have to deal with that uphill battle.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: He wanted me to be able to get deals and with brands and stuff... GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Because he saw my potential.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: And he knew that brands would hold that against me.

GATES: Of course.

GRINER: Like, not saying that it was right, but like, I can understand.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: You know, because at first, I was just upset, like, why is my dad like, like he don't love me?

GATES: Right.

GRINER: Like he, he like, is he disappointed in me?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: But it was more so he just didn't want me to have to deal with that.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: That uphill battle.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: And you could tell it didn't really put that much of a hindrance in between us, 'cause he was at literally every single game.

GATES: Yeah.

GRINER: And now, I mean, you see us now, we're, we're great, you can't separate us.

GATES: My two guests have achieved incredible success both on and off the court, but along the way, they've had little time to learn about the ancestors who may have laid the groundwork for their accomplishments, that is about to change.

I started with Chris Paul and with his paternal grandmother, a woman named Charlena Sloan.

Charlena has been Chris's biggest fan for as long as he can remember.

And the two share a profound bond.

PAUL: My grandmother is, uh, she's everything.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: You know, and, um, she, man, I'm tripping.

So, um... she calls or texts me after every game.

GATES: Oh, wow.

PAUL: And she's in North Carolina, obviously, I play for the Clippers on the West Coast, all these teams on the West Coast.

So, if my game starts at seven o'clock Pacific time, that's 10 her time.

GATES: Right.

PAUL: My grandmother watches every game, and she texts me or call me after every game.

GATES: Huh.

PAUL: Every game, I could pull out my phone and show you our text thread after the games.

And she, um, has just always been a constant.

GATES: Wow, that's a blessing.

PAUL: Oh, absolutely.

GATES: Chris's grandmother was born in 1944 in Anderson County, South Carolina, and we were able to trace her roots in that county back more than a century, all the way to a man named James Clinkscales.

James is Chris's fourth great-grandfather.

We found him in the 1870 census for Anderson County, living with his parents, Zachariah and Sina Clinkscales.

PAUL: Dang.

GATES: So, you just read the names of your fifth great-grandparents.

Great-great-great-great- great grandparents.

PAUL: That's crazy.

GATES: So, first of all, what's it like to see that?

You, you carry DNA from all those people.

PAUL: Man, it's, um, it's wild.

Uh, we had this question, uh, at our house the other day, where we was talking about if you had the choice, would you go back and learn who your great-great-great-great- grand people were?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Or would you rather go in the future and learn who your kids-kids-kids- kids-kids are?

GATES: Okay, what did you say?

PAUL: I said, I wanna go back.

GATES: Yeah.

PAUL: I said I wanna go back and to actually be sitting here, actually going back, that's wild.

GATES: Unfortunately, this story was about to take a painful turn.

Zachariah and Sina were both born around 1815 in South Carolina, which means almost certainly they both were born into slavery.

Searching for evidence of their lives, we focused on a White slave owner with their same surname, Mary Clinkscales.

In the 1860 census, Mary filed a slave schedule indicating that she owned 13 human beings.

There are no names on this schedule, only the color, gender, and age of each enslaved person.

But given what we knew about Chris's family, several entries stood out.

PAUL: One mulatto male, age 49.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: One mulatto female, age 39.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: One mulatto male, age 12, one mulatto male, age seven, one mulatto male, age four.

GATES: We strongly believe that you are looking at your fifth great-grandparents, Zachariah and Sina, their three sons, as well as your fifth great-granduncle, Robert "Bob" Clinkscales, listed there as property with no names.

PAUL: That's, that's crazy, so you'd be right there, enslaved with your kids.

GATES: Mm-hmm, oh, yeah.

PAUL: What would they have a 4-year-old doing?

GATES: You know, maybe bringing a cup of water to people, you know, they're growing into the job, so whatever the lowest level task was, they would give it, give it to the children.

PAUL: And as a mom, how are you able to take care of these kids?

GATES: Yeah, well, precisely.

How do you think it was possible for Zachariah and Sina to raise a family together in enslavement?

And think about this, knowing at any moment since you had no control... PAUL: They could take them.

GATES: They could be taken and sold down the river.

PAUL: Yeah, I think about, um, how protective I am of my kids.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: And, um, I cannot imagine them having three kids, 12, 7, and 4, and probably seeing the things that might have been done to them... GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: You know, and powerless, and you can't do nothing about it.

GATES: Regrettably, the relationship between Chris's family and the family that enslaved them did not end when freedom came.

We uncovered a labor contract from the year 1866, it shows that Mary Clinkscales hired Chris's ancestors to work her plantation under what was known as a share wage agreement.

These agreements were common across the Jim Crow South, and they were not favorable to the formerly enslaved men and women who signed them.

PAUL: "These said, free persons agreed to board and clothe themselves and to obey all orders from said owner of plantation or her agent and also do hereby agree to work for the said Mary Clinkscales in the capacity of laborers and faithfully, honestly, diligently and to the best of their skill and abilities to perform such labor in the care of said plantation."

Signatures, Zach, his mark, Sina, her mark, Bob, his mark, James, his mark.

Wow.

GATES: This is very likely the first labor contract that anyone on your entire Clinkscale, branch of your family tree, ever signed.

And it was the first time they were ever at least theoretically compensated for their work.

What do you think that meant for them, that moment?

You remember when you signed your contract?

PAUL: Yeah.

GATES: This is their contract.

PAUL: That's a whole different feeling.

GATES: Yeah, a whole different feeling.

PAUL: Yeah, I'm still processing.

GATES: According to this agreement, Chris's ancestors were to work Mary Clinkscale's land at her direction, much as they had under slavery, and they were to be paid not with cash but with a portion of the crops.

PAUL: That's crazy.

GATES: I mean, you're free technically... PAUL: But... GATES: ...does that sound like freedom?

PAUL: Not at all.

GATES: No, and in a good crop year, share wages could offer better returns than cash wages.

But in a bad crop year, share wage laborers did very poorly, and your ancestors had very little control over how the crop would turn out.

They were rolling the dice, and on top of that, people working on shares had to pay for their own food and clothing during the year while they're waiting on the harvest, right?

PAUL: Yeah, they was basically just working to stay alive.

GATES: You got it, it was called slavery by another name.

PAUL: That's crazy.

GATES: Chris, what's it like to know that your ancestors had to go through that?

You know, imagine you get the news, we're free, finally, we're no longer property, and then they're thrown into, um, a labor contract like that.

PAUL: It literally makes me think about, um, how strong their minds had to be.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Like their will, um, it would've been so easy to give up.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: But given their situation, they, whether they complained or not, they, they figured it out.

GATES: Chris is correct.

Zachariah and Sina did indeed figure it out.

They likely worked at least 10 hours a day, six days a week, growing cotton.

But they survived, and they moved their family forward.

Incredibly, by 1880, their son James even had a small farm of his own.

What do you think kept your fifth great-grandparents going?

'Cause after all, if they hadn't gotten up, done the 10 hours in the field, there'd be no Chris Paul.

PAUL: Yeah, to me, it, immediately goes back to like how they had to be wired.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: You know, and the perseverance, the ability to, to fight through, and the ability to, I can't imagine like being able to, I guess, see the bigger picture.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: And knowing that whatever they endured at the time, that hopefully it would mean a better life for their kids.

GATES: Right, a better day's coming, and for my grandkids.

PAUL: It puts stuff into a whole different type of perspective.

GATES: Much like Chris, Brittney Griner was about to gain a new perspective on an entire branch of her family tree.

Following her maternal roots, we traveled from Brittney's hometown of Houston, Texas, to New Orleans, Louisiana, and introduced Brittney to her third great-grandmother, a woman named Catherine Neal.

GRINER: Oh, wow.

GATES: You've never heard this name before?

GRINER: Mm-mm.

GATES: Well, Catherine was born around May 1868, three years after the end of the Civil War in Louisiana.

In 1883, when she was about 15, she married a man named Felix Balthazar.

And Felix is your third great-grandfather, your great-great-great- grandfather Felix Balthazar, ever hear of him?

GRINER: No.

GATES: Did you know you had roots in New Orleans?

GRINER: No, I thought it was just... GATES: You do.

GRINER: Yeah, I didn't know that.

GATES: Did you think we'd get back this far, this quickly?

GRINER: Nah, I didn't think it would go like this.

Honestly, I'm like shook right now.

GATES: Catherine and Felix had at least nine children together, including Brittney's great-great-grandmother, Laura.

But sadly, five of the children died in infancy.

And in the Louisiana State archives, we saw that Catherine's health suffered as well.

GRINER: "State of Louisiana versus Catherine Balthazar.

In this case, it is ordered judge and decreed that the said Catherine Balthazar be declared insane and that she be incarcerated in the state insane asylum at Jackson, Louisiana."

GATES: Any family stories about this?

GRINER: No.

GATES: Yeah.

GRINER: None at all, that's wild.

GATES: In 1898, Catherine was committed to the East Louisiana State Hospital, segregated state-run mental hospital located in Jackson, Louisiana, and you could see photos of it from the early 1900s on your left.

GRINER: Wow.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

GRINER: I mean, that makes me very upset that somebody in my family had to go through this, and the family members had to, had to go through this too, seeing her in there or not seeing her in there, I don't know if they, you know, they would even visit her.

GATES: The hospital's files show that Catherine was committed in 1898, released, and then readmitted two years later.

The files also contain a transcript of an interview that a doctor conducted with Catherine, offering a harrowing glimpse into the kind of care that she was receiving.

GRINER: "What kind of place are you in?"

"Kind of a storeroom."

"Are you crazy?"

"That is what they say."

"Did you ever see any ghosts?"

"Yes, sometimes."

"Was it a White or Negro ghost?"

Wow, that's crazy, um... GATES: Isn't that cold?

GRINER: Nah, just so old.

This is wild, um, I'm sorry.

"They were White."

"What did they say to you?"

"They didn't say much."

"Try to be good."

"Did you ever see God?"

"No."

GATES: Those are your ancestors' actual words.

How does it feel to read that?

GRINER: I mean, the answers to these questions are, are weird.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: And then the questions, too, though, honestly, like, I feel like the questions are weird, too.

GATES: You mean like... GRINER: I mean, mean... GATES: "Do you see, you see Negro ghosts or White ghosts?"

What kind of question... GRINER: Exactly, I mean, that was a weird one, I mean.

GATES: Right.

GRINER: That was a weird one.

And then did you, "Did you ever see God?"

I'm just like, okay, I'm not saying someone couldn't, but it's a very hard thing to prove.

GATES: We don't know why Catherine was asked these questions or how to interpret her answers, but she would never leave the hospital.

She died within its walls in 1939, more than 40 years after she was committed.

How does it feel to learn this?

To learn that you're, I mean, you were incarcerated, your ancestor was incarcerated.

GRINER: Yeah, she was legit incarcerated, is what happened to her.

I mean, I, I hate that that happened to my ancestors.

I thought I was the only one, honestly, um, that had been in like that.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Um, I just hate that she had no voice.

No wonder I love, maybe it's just embedded in me the fact that I want to give people voices that didn't have voices, but maybe there's a deeper reason to why I feel like that.

This could be it.

GATES: Digging deeper into the past, we encountered another story that resonated with Brittney's life today.

It begins over 100 years earlier with her seventh great-grandparents, a couple named Marie Coincoin and Pierre Metoyer.

Records show that Marie was born into slavery in Louisiana around 1742, while Pierre was a White man born in France around the same time.

They met in Louisiana in the 1760s when Pierre leased Marie from a neighbor so that she could work in his home.

Over the next 10 years, they would conceive several children together, a fact that outraged a local priest.

So much so that he filed a complaint against the couple.

Reading it over, Brittney began to have serious reservations about Pierre's treatment of Marie during those 10 years.

GRINER: I mean, the fact that she was, what loaned out basically to, uh... GATES: She's a slave!

GRINER: She's literally a slave.

And I mean, was it against her will at first, and then she fell for him?

Or was it she felt mutual?

Like those are the questions that are going through my head.

GATES: We don't know how it started.

GRINER: Mm-hmm.

GATES: But we know how it ended.

GRINER: Mm-hmm.

GATES: Okay?

Please turn the page.

GRINER: I know I got a lot of questions when I get home.

(laughs).

GATES: This is the same record we just showed you, only we've highlighted a different portion.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

GRINER: "Coincoin and, and Metoyer..." GATES: Mm-hmm.

"In whose house and company, the said unmarried Negras has produced five or six mulatto children, not counting the one with whom she is now pregnant."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: "This cannot happen in the house of an unmarried man and an unmarried woman without the public thinking and judging there to be illicit intercourse between the two partners in concubinage."

GATES: You got it.

GRINER: "From, from this, there has ensued a great scandal and damage to soul."

GATES: "Damage to soul."

GRINER: "Damage to soul."

GATES: This White man is living with his lover, they have, uh, six children, right?

GRINER: Mm-hmm.

GATES: And this priest is going nuts.

And he files a complaint against him, I mean, their priest has said, this is a sin in the sight of man and God.

And they said, we got to do something about it.

GRINER: I know that priest was losing it, his wig, oh my God.

GATES: We have no idea how Brittney's ancestors felt about the priest's accusations, but we do know how they responded.

In July of 1778, less than a year later, Pierre purchased Marie from her owner, and then he freed her.

GRINER: Ooh.

GATES: What do you think that was like for Marie finally to get her freedom?

GRINER: I mean, I would think she would feel safe, this man has done everything for her, honestly, like she has a family through him.

He bought her and set her free and made sure she had her freedom.

GATES: Um, there are a lot more cases of a White male... GRINER: Mm-hmm.

GATES: ...fathering children with a Black woman who was never freed.

GRINER: Yeah.

GATES: Now, Brittney, did he love her or not?

GRINER: He loved her.

GATES: Although Marie was now a free, she and Pierre still faced a terrible problem.

They had seven children who remained in bondage because the law dictated that the children of an enslaved woman followed the condition of their mother, and thus were the property of her owner.

Even if the man who had fathered them was free.

Fortunately, Pierre had a solution.

He did what the law demanded and purchased each of his children and emancipated them, securing his family's freedom for generations to come.

GRINER: Now, that's a story.

GATES: That's a story.

GRINER: That's, that's a story, that's a story I can be proud of, honestly.

And, um, it made me think those 10 years were not hell for her now.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Like to someone that did all that and then to go buy the seven children, um, as well to go above and beyond, and do that as well, let's you know, like he actually did care.

Like, at some point his mind changed and I can respect a family member that, that does that.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Like, yeah, you had some bad intentions maybe potentially in the beginning, but I see you made a change.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: I can respect somebody that makes a change.

GATES: Like Brittney, Chris Paul was about to meet an ancestor who'd completely changed the trajectory of his family.

The story begins in Winston-Salem, North Carolina, with Chris's fourth great-grandfather, a man named Peter Oliver.

Chris had heard of Peter before.

Indeed, he knew that Winston-Salem had long been planning to name a park after his ancestor, but Chris wasn't sure what Peter had done to deserve such an honor.

The answer lies in the archives of a North Carolina branch of the Moravian Church.

In 1786, this church purchased Peter from a slave owner in Virginia and then baptized him, likely at his own request.

PAUL: And who gives the name... GATES: The Moravians?

PAUL: Peter, the Moravians?

GATES: Yeah.

Now, we don't know if he said, "I wanna be Peter."

PAUL: Right.

GATES: Or if they said, "Your name is Peter."

PAUL: But he got the name from the Moravians.

GATES: Yeah, in that moment of baptism.

Initially, he was known simply as Negro Oliver.

Then, when he's baptized, he takes on the Christian name Peter.

And after 1786, he's known as Peter Oliver.

How do you think he felt that day?

PAUL: Probably felt about as normal as he possibly could.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: I mean, as, as normal as you could in 1786.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: But to actually have a name and not be called "Negro."

GATES: Right, right, right.

PAUL: It's wild.

GATES: The Moravians were unusual in that they allowed enslaved people into their congregations and treated them as religious, if not necessarily as social equals, providing opportunities generally unavailable to other enslaved people.

For Peter, these opportunities would prove life-changing.

Roughly a year after his baptism, he was purchased by a master potter named Rudolph Christ.

Pottery was a valuable craft at the time, and Peter would rapidly excel at it, becoming one of the only documented African American potters of his era in all of North Carolina.

PAUL: This is, wild.

GATES: What's it like to see that?

PAUL: Man, it's just so much connectivity.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Right, and you realize everything happens for a reason.

And the stories that we sort of all tell about ourselves, we're always connected to, to something, something that came before us.

And it's amazing to hear, right?

Like this is a different connection with Peter Oliver then just sort of like a, a park being renamed... GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: ...in our, in our hometown.

GATES: And, um, even though I wasn't in slavery or anything like that, like I, the way he used pottery is kind of how I looked at the game of basketball.

GATES: That's right.

PAUL: You know what I mean?

And it's been able to take, uh, me and my family outside of our hometown and show us the world.

GATES: Mm-hmm, a skill.

PAUL: Yep.

GATES: At which he excelled.

PAUL: Yep.

GATES: And which the society placed value on.

PAUL: For sure.

GATES: Moravian records show that by 1799, after just 13 years in their congregation, Peter had not only mastered pottery, he'd also joined a choir and a firefighting team.

And he'd done something else as well.

Something that must have required extraordinary effort.

Chris, he'd also learned to read and write.

(laughs).

PAUL: He was different.

GATES: He was a bad brother, man.

PAUL: Yeah.

Especially 'cause reading and writing was sort of forbidden.

So, when, it makes you wonder, when was that taking place?

Who was teaching him?

GATES: Right.

Well, his master was saying, obviously, he's so bright, let's teach him to read and write.

PAUL: Right.

GATES: He probably said, "Look, I'm more valuable to you if you let me learn to read or write."

PAUL: For sure.

GATES: You know, did the rope-a-dope on him.

PAUL: When did he have time to do all this?

GATES: Unfortunately, despite everything he'd accomplished, Peter remained enslaved.

But that was about to change.

In 1800, he was sold yet again, this time to a Moravian man who lived in Lancaster County, Pennsylvania.

And we believe that Peter himself pushed for this sale.

PAUL: So why to Pennsylvania?

GATES: Please turn the page.

Chris, you're looking at an amazing document.

It's an affidavit presented to a man named Frederick Kuhn, one of the associate judges in Lancaster County, would you please read that transcribed section?

PAUL: "Peter Oliver verily believes that he is entitled to his freedom by virtue of the laws of Pennsylvania, having been held as a slave by virtue of the said bill of sale in this commonwealth.

And that deponent is not confined or restrained of his liberty for any other cause whatsoever.

And further said not.

Signed, Peter Oliver, sworn before me, June 13th, 1800."

GATES: He goes to a judge and says, "Your honor, I believe that I am a free man in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania."

PAUL: And that was part of probably why he got sold up to Pennsylvania.

GATES: Bingo, that's right.

PAUL: Right.

GATES: They were enabling his freedom.

PAUL: Yep, yep.

GATES: Because Pennsylvania had abolished slavery.

PAUL: Had abolished slavery, right.

GATES: And North Carolina didn't abolish slavery 'til the Civil War made it abolish slavery.

PAUL: They did him basically a favor in se, selling him... GATES: That's right.

PAUL: ...up North.

GATES: Isn't that amazing?

PAUL: Yeah, yeah, absolutely.

GATES: There is a final beat to this story.

In 1802, less than two years after winning his freedom in Pennsylvania, Peter returned to the south, got married, and settled on a four-acre farm that he leased from the Moravian Church outside of Salem, North Carolina.

PAUL: Wow.

GATES: He goes back to North Carolina, which is why your family is from North Carolina.

PAUL: Is why my family's from North Carolina.

GATES: Yeah.

PAUL: So, he went up to Pennsylvania... GATES: Got his freedom.

PAUL: Got his freedom.

GATES: And said, "I'm going back home."

PAUL: Came back down.

GATES: So, he must have loved North Carolina, 'cause me, I would've stayed in Pennsylvania.

PAUL: Right.

GATES: What do you make of this?

PAUL: It's, uh, even more meaningful now, 'cause of course, you know, of your immediate family, I always knew that I was born and raised there, but knowing that it traces back all the way to... GATES: 1802, it's amazing.

PAUL: Yeah.

And to move away and to come back, um, what he demonstrated is exactly why they put in a, a park and all of that.

GATES: Yes.

PAUL: In Winston.

GATES: Yes.

PAUL: You know, and the importance of this is, I mean, I remember my mom getting on Zooms with the family members or whatnot, talking about Peter Oliver and me, I'd be like, okay, okay.

You know, but you don't know what you don't know.

GATES: No, of course.

PAUL: Right, so... GATES: Yeah.

PAUL: ...to hear all of the information that I heard today, it makes me understand why.

Yeah, he was a go-getter.

GATES: We'd already traced Brittney Griner's mother's roots in Louisiana, a place she'd never associated with her own family.

Now turning to her father's ancestors, we found ourselves on more familiar terrain.

Brittney's home state of Texas.

The story begins with Brittney's great-great-grandfather.

A man named Henry Adams.

Brittney knew that she has relatives who still carry the Adams surname, but she had no idea where it came from.

We tried to learn and ended up back in the slave era, poring over the estate records of a White Texan named Thomas Adams, Sr.

They list 36 enslaved human beings, among them is a boy named Henry, worth $125.

A site that caused Brittney to recoil.

GRINER: I mean, seeing a value placed on any person is just it's like, I can't even really imagine it.

I can because I know the history and the sick history, but to see that it's just, I mean, it's just a boy.

It's just a kid.

Henry was around two months old.

GRINER: Mm.

And I got a seven-month-old at home, I couldn't imagine him being born into this like... (heavy sigh).

And the Adams Sr... GATES: Yep.

GRINER: Deceased.

So got the name from slave owner.

GATES: Yep.

There's your great-great-grandfather Henry listed as the property of a White man named Thomas Adams, Sr., given a value in an estate record, just like you would do a sofa or a cow or a horse.

GRINER: I'm literally gonna say a cow, a pig, a animal, like... GATES: Yeah.

GRINER: Like that's just sad.

I mean, two-month-old, I mean, like, ain't even started life yet.

GATES: No.

GRINER: Already belonging to somebody else.

GATES: Thomas Adams, Sr., was one of the wealthiest men in his county.

When he died in 1859, he was worth around $40,000 or roughly $1.5 million in today's money.

A big part of that wealth was human property.

And as we combed through his estate records, we came upon Henry's parents, Sam and Pallas Adams, as well as a curious detail.

According to this record, Sam was 32 years old, and Pallas was 12, and they already had a child, your great-great-grandfather Henry.

But we puzzled over this, we don't know if Pallas's age is correct... GRINER: Yeah.

GATES: ...there, her age on census records suggest that she was about 25, not 12.

So, we can't be sure.

GRINER: Okay.

GATES: But it's possible that Pallas had Henry before her 13th birthday.

I mean, it's possible.

GRINER: I mean, it wouldn't be uncommon back then; it wasn't like they'd cared.

Uh, I mean, people had kids way earlier, but that's crazy to think that she was already, she had already lived that much life at 12, 13.

GATES: This story was about to take an even more troubling turn; Thomas' estate records were filed in January of 1859.

Meaning that his slaves were divided up amongst his heirs more than six years before the abolition of slavery, which raised a chilling question... So, what do you think happened to your family?

Were they able to stay together, or were they split up?

GRINER: Oh, they all got split up.

I mean, they probably took joy, and I know they; some people took joy in splitting up families 'cause they didn't want... GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: ...them to be together, have a sense of all you supposed to do is work.

I don't need you worrying about your wife, your kid, or any of that.

GATES: Right.

GRINER: Work.

So, I'm, I wouldn't be surprised if they didn't split up every single person on here.

GATES: Please turn the page, let's see.

This is the same estate inventory we just showed you, only we've highlighted a different portion.

Would you please read that transcribed section?

GRINER: "To Abel Adams."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: "Pallas age 12 years."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: "To Harmon Adams."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: "Henry age two months."

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: "To Thomas Adams, Jr., Sam, age 32."

GATES: You were right, your family, even the two-month-old baby separated from his parents.

Your ancestors were split up among three different sons of their enslaver.

Pallas goes to Abel, Henry to Harmon, and Sam to Thomas Adams Jr.

GRINER: Inhumane.

It makes me look at the people that we got this name from, like we, we literally took a name from these inhumane people.

GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: Makes me look at the name Adams so different, and I know there's some really good Adams out there on my side of the family, but it makes me look at that name differently, of where we got it from.

GATES: Happily, Brittney's ancestors were able to reunite when freedom came.

In the 1870 census, they were all living together in the same household.

But this census also tells us something far less joyful.

Just a few doors down from Brittney's family lived a man named Fabian Adams, one of the sons of Thomas Adams Sr.

The very same man who had enslaved them.

How about that?

While, Fabian didn't inherit any of your ancestors from his father's will, the fact that the families were living so close five years after the end of the Civil War suggests that your ancestors, even though they were free, still had to work for the people who had held them in bondage.

GRINER: Oh, 100%, when I saw that occupation, farmer White.

And then I see farm laborer, farm laborer, oh yeah, they was definitely still working there.

GATES: Can you imagine living next to the people who used to own you?

GRINER: And not getting paid properly either, probably.

GATES: Sharecropper.

GRINER: Yeah.

GATES: "Here, here, boy, put that X there."

GRINER: You know, that's all, they just knew the new, new age slavery, that's all it was for them.

Like, that's crazy to still live there, just the trauma of that knowing, 'cause they, I mean, they lived it.

They were separated, brought back, spread out through the siblings, brought back together.

Fabian didn't own any, but he's definitely benefiting from y'all working there now.

GATES: And you know, like it or not, and it shouldn't surprise us, but most formerly enslaved people stayed where they had been enslaved because they didn't have a choice.

They couldn't read, they couldn't write, that was illegal, the system was rigged against them.

GRINER: Yep.

Where were they supposed to go with what money?

GATES: Brittney's questions are good ones, and the answers would prove sobering.

Her ancestors would not leave the county where they'd been enslaved for almost a century.

But that doesn't mean that they wouldn't make progress.

By 1910, less than 50 years after the end of the Civil War, her great-great-grandfather, Henry, had not only managed to become a landowner, but his children had too.

And seeing the journey of her family laid out from slavery to freedom would prove deeply moving to Brittney.

Your people are survivors; you feel a connection?

GRINER: I feel a deep connection.

It just makes me understand myself a little bit more.

Like knowing my background, my history.

You, you think you're blazing your own path in life, but you're really kind of like reliving some of the things and some of the choices, even places where you're living that your ancestors went down.

GATES: Yeah.

GRINER: And it's kind of cool to walk the same road that they, they walked in the same sense.

It was a hard road they walked, but I mean, I wouldn't be here today if they wouldn't have, have walked this road.

If any of these little small things would've changed, a husband not been somebody's husband, they would've fought, they would've ran, you know, tried to escape.

It could have altered everything, and I could not be here.

GATES: That's right, poof.

GRINER: Yeah, you know, as much as I want all this to change and just be all happy-go-lucky without this happening, I might not be here right now.

GATES: That's right.

GRINER: So, um, I'm super appreciative of this information, that's for sure.

I know my family is gonna be very appreciative of this.

GATES: What's your father gonna say?

GRINER: He gonna be blown away.

I already know he's gonna be, he's gonna be shocked, he's gonna be like, "What?"

He, he's gonna try to figure out how, how y'all figured all this out.

(laughs).

GATES: The paper trail had now run out for each of my guests.

It was time to show them their full family trees.

PAUL: Oh, my goodness.

GATES: Now filled with names they'd never heard before.

GRINER: This is awesome.

PAUL: Yeah, I'm gonna put this up in my house.

Thank you, thank you.

GATES: For each, it was a moment of joy, offering the chance to connect with the women and men who laid the groundwork for their success.

PAUL: To see this is the wildest thing ever, I think it just makes, makes me appreciate things a lot more, right?

GATES: Mm-hmm.

PAUL: Even though I know I should already, but just understanding what many generations have went through before me in order for me to be sitting right here with you.

GRINER: My ancestors had some fight in them.

Um, to, to make it through, to push through living next door to the people that had them enslaved... GATES: Mm-hmm.

GRINER: To being put in a, in a insane asylum and having to deal with that and cope.

Uh, it definitely helps me understand me a little bit more.

GATES: Yeah.

GRINER: My fight, it all comes from, from my family.

Everything that I've been through, everything I've gotten through, how I've gotten through it, it makes sense.

GATES: That's the end of our journey with Brittney Griner and Chris Paul.

Join me next time when we unlock the secrets of the past for new guests on another episode of "Finding Your Roots."

Brittney Griner Learns the Origin of a Family Name

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep5 | 3m 58s | Brittney Griner discovers the origin of the "Adams" name on her father's side. (3m 58s)

Chris Paul Discovers His Family's Southern Ties

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S12 Ep5 | 3m 49s | Chris Paul discovers the first labor contract his paternal family ever signed. (3m 49s)

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S12 Ep5 | 30s | Henry Louis Gates, Jr. maps the roots of basketball stars Brittney Griner and Chris Paul. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- History

Great Migrations: A People on The Move

Great Migrations explores how a series of Black migrations have shaped America.

Support for PBS provided by: