Vivien's Wild Ride

Season 27 Episode 4 | 1h 24m 45sVideo has Audio Description

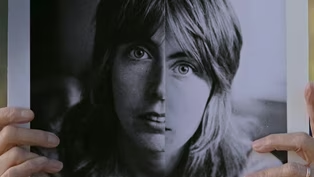

When her eyesight begins to fade, a film editor reimagines belonging and what it truly means to see.

When legendary film editor Vivien Hillgrove begins losing her sight, she confronts memories of loss and resilience while reinventing herself as an artist with a disability. From her groundbreaking career in cinema to her life on a small farm with her partner, Karen, Vivien’s story reveals how creativity, care, and connection can reshape what it means to see and belong.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Vivien's Wild Ride

Season 27 Episode 4 | 1h 24m 45sVideo has Audio Description

When legendary film editor Vivien Hillgrove begins losing her sight, she confronts memories of loss and resilience while reinventing herself as an artist with a disability. From her groundbreaking career in cinema to her life on a small farm with her partner, Karen, Vivien’s story reveals how creativity, care, and connection can reshape what it means to see and belong.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Independent Lens

Independent Lens is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

The Misunderstood Pain Behind Addiction

An interview with filmmaker Joanna Rudnick about making the animated short PBS documentary 'Brother' about her brother and his journey with addiction.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipPart of These Collections

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship♪ [birds singing and insects chirping softly in the distance] [horses whinny] [a soft buzz of insects, birds, and breeze] [a distant sheep bleats] [footsteps crunch dry grass] [carpet muffles footsteps as birds continue singing] I'm really happy I dropped acid in the '60s.

[a mourning dove calls] It sort of prepared me for this unusual visual world I currently inhabit.

[tender, slightly dissonant music begins on piano, grows] [booming whoosh of cars] ♪ [tender music is orchestral now, accented by whooshing cars] ♪ [music softens, wheels scrape the rough road] When I was a young kid, I loved playing with mechanical things.

Like, I built my first skateboard when I was 16 and skated down from the Cliff House to the ocean.

[music bright and energetic, cheery yells on carnival rides] And I loved how the equipment worked at the fun house.

These stairs that blew up air and that these rounding things and centrifugal force and all the incredible things at Playland at the beach.

[music becomes curious, rollercoaster clacks and rushes] How does this whole thing go together?

How do the parts go together?

And I think that's a... a lifelong thing.

It's like maybe I ended up as an editor like, how does all this [bleep] go together?

[music turns pensive, fluttering layers and chords] [music fades to the clacking whir of a film projector] As a film editor, every little detail on the screen is important to me.

[skate stamps in time to a jazzy rhythm on bass] I love editing and being part of telling the character's story.

[melody builds with a jazzy-lounge vibe] In the '80s, I edited dialogue.

I got to work with some of the most groundbreaking directors of the time.

[music continues, trumpets building chords] [click] The '90s, it was picture editing.

[film reel whirs as jazzy-lounge music continues] And then I fell in love with documentaries.

[music mellows, a pensive melody on piano] You just take this raw material, 4-500 hours of film, and what part of that has got the juice?

The thing that is the most exciting about it is the story that's behind the obvious story.

The story that you're weaving in the background of putting the pieces together in this wonderful jigsaw puzzle of personalities and beliefs and mythologies.

[music is gentle, tender and lilting] I fall in love with all the characters I work with.

[a child giggles softly] [bird chirping echoes the giggles] And then after decades of being in this fantastic career, peculiar things started to happen.

Should I do.... [key beeps on press] Whoops.

Well, it's not that.

It's.... [springy keys clack] I was having a really tough time reading.

I'm missing like three letters out of a seven-letter word.

[music is soft and haunting] The words were floating around.

I just thought, am I losing my mind?

Do I have Alzheimer's or something?

[suspense builds in haunting music] The ophthalmologist said, You have dry macular degeneration.

And you're losing your central vision.

I'm losing... my sight.

There's no cure.

[haunting music continues with an ethereal hum] Who am I... without the visual world?

[faraway bustle of the city, birds singing] [clap] [slow individual claps] [claps gently fade] DR.

HIRSHFIELD: This is the Living with Vision Loss class.

We'll go into how the vision loss has changed your life.

Getting it out... is the first step towards getting back in control of our lives.

ROBERTA: I think the hardest part is the friends and family who call and say, How's your vision?

How you doing?

You getting better?

What are you doing to get it better?

It's not going to get better.

It doesn't go that way.

GREG: My biggest problem is dealing with the overwhelming degree of loss.

I don't like knowing that I'll never see my kids again.

FARHAD: I was the one I used to take care of the whole family.

Now, it's the other end of it [chuckles] is people have to take care of me.

I like to give.

I don't like to receive.

VIVIEN: My identity is so wrapped up in being a film editor.

And it's all visual.

And then I started to lose my sight.

And it was this overwhelming feeling.

It just, all of a sudden, I just felt like I was drowning.

[gently pulsing music] The center of my vision is beginning to disappear.

And it feels like I take my peripheral vision and move it over the middle to cover the hole.

[gentle music fades to an aching lullaby] Objects in front of me appear and disappear as I fill in the blanks.

People's faces are starting to look like a Picasso.

And the Picasso face is so unnerving that I look away.

And as soon as I look away, they look away.

And I've lost them.

[stirring vocalizations join the lullaby] And this loss feels so familiar to me.

[lullaby fades] [syncopated old-timey jazz tune on piano] ♪ [tune continues on piano] I grew up in this very suburban house.

I was the eldest of five.

And everyone called me Bunny.

[a child laughs] And I felt like the kids, I felt like they were like my kids on some level.

When my dad came home from work, he would walk over to the piano, sit down, and begin to play.

[tune becomes more animated] There was this freedom in him.

And we all would go bananas and run around the house and scream and yell.

My mother loved it.

She would laugh and embrace the craziness.

[lively tune on piano continues] Music was bringing in so much joy.

[music gathers energy, children giggle with delight] When we went outside, it really was different.

I was painfully shy... but not when I skated.

I would, like, come into my body and feel the music that was in our house.

I would feel so free and alive.

[tune winds down with a flourish] [film projector clicks to life, film whirs through] OLD FILM NARRATOR: Johnny and Janie are not yet quite grown into manhood and womanhood.

They are in between.

And the in-between period is known as puberty.

This name is used to describe the physical growth and change that bring sexual maturity.

VIVIEN: As I was growing up, mom never talked to me about puberty or sex or anything like that.

[solemn music] It's 1964.

No birth control for unmarried women.

And abortion is illegal.

[solemn music continues, bright tones layering on] [staticky channels changing on a radio] [stirring ballad with electric guitar] High school.

A boy.

One night.

[a high, piercing note on guitar] [tender chords on electric guitar fade] I just thought everything was natural.

I didn't feel bad until... "Oh, my God, you're pregnant."

It's like it just seemed like the whole [bleep] sky fell down then.

[hum and rush of traffic] And then my father drove me to Grandma's and said, You're gonna be staying with her for a while.

[elevator quietly rumbles, wistful music] [wistful music continues] I'd always wanted mom and dad to be proud of me.

And here they had to hide me away.

I felt such shame for... bringing this upon my family.

I felt so alone... waiting for Grandma to come home from work.

And then all of a sudden, my parents picked me up.

[music sweeps, hisses to a stop] [silence] [very distant hum of traffic] [haunting hum like far, howling wind] I have a little bit of amnesia about that place.

But when I went in there... I was actually so relieved to be at a place with other girls who were like myself.

I made friends with this girl who could play piano.

And so, we would sneak out and go to the rec room, and she would play these amazing things that were classical pieces and jazz.

And I would rock back and forth in my chair, and I would just [voice cracking] be back home.

[sweeping, soaring music on piano and strings] ♪ [music softens, train clacks along track] MAN: Who is the unwed mother?

Is she a tramp?

A neurotic?

The girl from the wrong side of the tracks?

Perhaps you may feel she is not the kind of girl you would want to invite into your house.

[slow, meditative melody on piano] VIVIEN: The doctor told me if I felt any contractions to get up to the third floor right away.

I remember holding the hand of a woman.

I felt safe if I could just hold on to that hand and not let it go.

[meditative music continues] And there were these beautiful lights.

I felt this overwhelming feeling... of connection to this life inside of me.

And then it felt like everything dropped out of me.

Everything went black.

[music disappears] [piano returns, now somber] Mom had said, Don't look at the baby.

There was a screaming in my head.

I looked through this window, and I saw this young girl picking up my daughter.

And everything in my cells said, [voice cracking] go in there and grab her.

[somber music continues, pulsing like a slow heart beat] I called my mom.

[dial clicks and whirs] And I just said, I can't do this.

I can't go through this, Mom.

I could feel my mom on the other end.

Then she just said, Oh, Bunny.

There was a really long silence.

[last chord on piano slowly evaporates] And I knew that the sadness we were both feeling was just too much for her.

[receiver clicks onto phone] [hum of cars passing, gulls squawk] When I read the adoption papers, I couldn't stop crying.

[softly howling wind] The social worker said, "You will shame your whole family if you don't go through with it.

And don't try to find her until she's at least 21."

[wind fades to birds chirping, a distant dog barks] My parents never mentioned it again, and nobody ever told my brothers and sister.

[laughter and conversation from down the hall] [contemplative music, melody on piano] [dress form clicks and clatters into place] [contemplative music continues, builds] I felt such shame for not standing up and fighting to keep my daughter.

[contemplative music continues] [music fades] [cane tip clinks and clacks along asphalt] [cacophony of traffic: rushing, rumbling, honking] Everything inside of me longs to make sense of this world without a center.

[traffic roaring, intriguing music] -In a clockwise direction, where is your least dangerous vehicle?

-Least dangerous vehicle.

Nobody's making a left anywhere.

Right, right-hand turns can be happening.

And it's very noisy.

-Right.

So you're thinking about it a little too much, okay?

-Okay.

-The least dangerous for a clockwise crossing is your near parallel.

[music continues pulsing, traffic humming] [crosswalk button beeps] [music fades, cane tip scrapes the road] [chorus of night insects, cane tip scraping] [slow, sweet melody on piano joins cricket chorus] [crickets fade as melody gathers energy] ♪ [slow, sweet melody fades to traffic] [slow Blues guitar solo] It is 1967.

I'm 21 years old, two years before Stonewall, and homosexuality is illegal in San Francisco.

[Blues music builds] And I walk into Maud's, this dark, cavernous lesbian bar that was filled with hidden women.

[conversations all around as Blues continues] It both frightened and thrilled me.

I'd always been attracted to women, but for the first time in my life, I felt rebellious enough to act on it.

There was sort of a criminal euphoria, a freedom.

[Blues fades into down-tempo, edgy tune] It was like I had been liberated from a archetype of woman that was so strict.

♪ [down-tempo music builds, orchestral with electric guitar] ♪ I lowered my voice.

I started wearing comfortable shoes.

I walked a little heavier.

And it's like I was willing to take up space.

[motorcycle roars past] [music slows and settles] I met a woman who was a filmmaker, and she said, "Would you do sound for me?"

And I said, "Sure, I'll do sound.

How do I do sound?"

[gripping music] She said, "Here's a Nagra."

And I went boi-oi-oing.

That is a fabulously designed machine!

[sweet, bright music] Everything was built as if it was a beautiful watch.

She recommends me for a job at Studio 16.

Denver Sutton, the owner, says, "What do you know about film?"

I said, "I know nothing about film, but I will work harder than anybody you've ever met," and I get the job.

So, I ended up doing the books, cleaning the bathrooms, shooting, mixing.

And editing was the thing that stole my heart.

[switches click] [slow, pensive melody begins, tape winding] [click and ring] [music brightens, brisk and plucky] [a whistled melody joins in] [levers release with a click-click-click] [music fades as tape and reel wind] [epic '60s Hollywood orchestral film music] Denver's specialty was industrial films and educational films.

And so, I got to work on some marvelous things like the Product Picker Packer, which was this incredible industrial about this machine that Crown Zellerback had of how to wrap toilet paper.

And so, it was not a terribly artistic beginning, but I loved every part of it.

[sultry jazz] WOMAN: Hello, police?

This is Jean Collier.

NARRATOR: Even though a caller is expected or a delivery man is well known, never answer the door unless you are fully clothed.

[Bebop jazz combo] VIVIEN: I would walk down Broadway every night on my way home from Studio 16.

Something was really comfortable about North Beach.

[Bebop jazz continues, chatting crowds and traffic] I had no reservations when I was asked if I would edit on several adult films.

[funky rhythm section] I went by the name of Lorraine Sprocket and worked on such distinguished films as Dingle Dangle , Frisco Fiasco , and Easy Come, Easy Go.

I was beginning to learn about the art of metaphor.

[mellow song on acoustic guitar and hand drum] Peculiar travel suggestions are dancing lessons from God.

♪ Everywhere I looked, artists and activists were breaking the rules.

There were all these experimental filmmakers coming through Studio 16.

It was like an awakening for me of what was possible in film.

[light, folksy guitar and hand drum] There was this time in San Francisco where everybody started taking their clothes off and shooting film.

And it was just like every time you turned around, there was somebody nude on camera.

And it was such a feeling of freedom, of acceptance and openness about our bodies that had been previously shamed.

[melancholy music] [light birdsong beneath melancholy music] ♪ Just under the surface, I still held this secret of relinquishing my daughter and the sadness of not being there with her as she's growing up.

I had told no one.

And I continued to wait for her to turn 21.

[music fades, birdsong continues] I'm having a really hard time revealing to my friends in the film community that I'm losing my sight.

I just don't want people to think I'm less capable.

[mixed bird calls and songs fill the space] This really lovely filmmaker that I know asked me to come to a screening of her film.

What I should've said was, "I can't see.

I can't see your film."

I couldn't say that.

And so, I went.

I left my cane at home.

[film projector whirs] It was a foreign language film, and I couldn't read any of the subtitles.

And the characters were like big blocks and shapes, and I couldn't see any of their faces.

[indistinguishable dialogue in Arabic from the film] What am I doing?

I'm pretending that I can see.

[soft, ethereal music] Losing my daughter and losing my sight feels so connected.

[passing cars hiss, slice through the space] -You used to be able to get in the car and turn the key and go anytime you wanted to go.

And you can't do that anymore.

-It's just this sense of you don't have the freedom that you had before.

And I think that's one of the biggest things is this loss of being independent.

Yes.

-Siri?

Open Uber.

[app beeps] SIRI: Closing error Uber.

VIVIEN: I'll just go.

[clicks from swiping] SIRI: Dictate.

CATHY: Correct.

I want you to listen to what it tells you because you're gonna forget what to do next.

You're so quick to single finger, double tap to start the dictation.

You're not taking the time to listen to what you need to do when you're done.

-Okay.

-So you're gonna touch the dictation button, and you're gonna listen to what it tells you to do.

SIRI: Dictate button.

Double tap to start dictation.

Double tap with two fingers when finished.

CATHY: When finished.

[tap, tap, chime] VIVIEN: Rohnert Park SMART train station.

[chime] SIRI: Inserted Rohnert Park SMART train station.

CATHY: Part of the process is learning how to slow down a little bit.

Because when you have usable sight, you just know where to go.

And as you start losing your sight, and you're still in that mode, like, well, let's just get right to it real quick.

You need to stop and take the time because you're no longer reading with your eyes, you're reading with your hearing.

[cane glides and lightly scrapes sidewalk] [ponderous music] [train bell rings steadily] ♪ [ponderous music continues, quiet chatting nearby] [announcement chime] ANNOUNCEMENT: For your safety, please watch the gap between the train and the platform.... CONDUCTOR: I don't know what direction you're gonna go, but I'll get you past the yellow stuff there.

VIVIEN: Okay, great.

Thanks, Hon.

Thank you so much.

CONDUCTOR: Step.

Here.

VIVIEN: Right there.

Okay, thank you so much.

[cane tip glides on sidewalk as ponderous music continues] [cars and buses clamor past] VIVIEN: Am I on 3rd Street right now?

SIRI: Getting directions to 3rd Street, San Rafael, Map.

Benjamin Moore.

VIVIEN: Can you tell me if this is 2nd Street or if...?

-Fourth.

-This is 4th!

Perfect.

Okay.

Is it okay to go now?

It must be because these guys are going.

I just gotta get back.

I'm gonna turn right, and then I'm gonna turn left and that'll get me back to the train station.

[a car honks twice, engines rev] [bells clanging, nearby conversations] [cars clatter over train tracks] Oh, good.

At least I know you're going, so I'm fine [laughs] to go.

[cane segments click] Okay, next time I'll have it wired.

[sighs] [subdued music, train squealing along the track] DR.

HIRSHFIELD: Each day there's something new that comes along and says, ah, ah, ah, you don't know this one.

And it's almost like I have to start all over again.

I get frustrated with myself about not being able to learn new stuff.

You have to be intentional about doing everything.

That's what blindness does to you.

It chips away at the things that you can do.

And you hold on to the things that you can do.

I went from being just a really gregarious person and lots of people around me to being really isolated and feeling alone and not figuring out how I could climb my way back out of this thing.

[music turns brooding] I remember when I took acid the first time.

I began to see my sadness in a totally different way.

[brooding music layers over hand drums, finger cymbals] [layers of music dance around each other] I began to see past this small box of my suffering, seeing myself as being part of something much bigger, this web of connectedness.

[layered music fades] [melancholy music] Everyone who has macular degeneration sees differently.

I have these blind spots and missing puzzle pieces that I fill in with what I think should be there.

Maybe these current visual distortions can be more than just a limiting disease.

[music fades] [expectant music starts, matched with slow claps] [slow claps continue] [claps now muffled] [music fades] [chorus of crickets punctuated by distant bird chirps] Discovering the world through sound is now this... crazy experience.

I'm beginning to see through hearing.

[overlapping, rapid tree frog songs] [high, piercing tone, then light laughter] [steps, baby lamb bleating, chickens clucking] [glittery raindrops pelting the roof, soft and hard] [wind chime in time with birdsong, rustling wind] [chittering song birds] [click] [rollers begin to whir] After years of working at Studio 16 on industrials and educational films, I started working on low-budget feature films for family entertainment.

So I was looking around for editing rooms, and I saw that Coppola had opened American Zoetrope on Folsom Street.

And I rented a room.

[squeal of tape rewinding] Like, I would walk down the hallway, and it was Coppola's The Conversation.

ACTOR:...kill us if he got the chance.

VIVIEN: Phil Kaufman's White Dawn.

-Saturday, May 17th, 18th.... VIVIEN: And all these mavericks that were about to change film history.

[Western-ballad-style tune with guitar and whistling] Eventually, I got a huge break... working with some of these trailblazers.

These guys were experimenting with everything.

[ballad fades to upbeat, tango-like melody] It wasn't just groundbreaking films that they brought into San Francisco, but a revolutionary shift in who got hired.

[upbeat tune continues] BARBARA: A lot of women were brought into sound post-production.

That was historic.

An unprecedented movement in film history because sound editing, sound mixing, sound recording had been a male province entirely up until really the '60s and '70s.

VIVIEN: Woo hoo!

[music fades] -Hi.

-Hi!

[delighted laugh] [kisses] -So good to see you, honey.

-Hello, my darling.

-Hi, dear.

-How are you?

Where did Sue go?

Sue!

-I'm right behind you!

-I can't [bleep] see!

What the hell?

-Oh, that's all right.

Hi, baby.

-Give you a big hug and tell you I'm Marilyn.

[kisses, kisses, laughter] -You look wonderful, if I could see you.

-Bonnie Koehler.

-Oh, Bonnie!

How are you?!

-How are you?

-I'm Terry.

-Oh, hi, Terry!

Good to see you again.

-So you have something that will sort of blow things up so that you can see it better?

-That and these.

All I have to do is, like... like put my head back and forth 'cause I'm not seeing anything out of the middle, but I can see a little bit out of the, you know, my peripheral vision?

-Yeah, yeah.

-I try to hold on to every little bit of eyesight I have.

I fly around here, like, you know, I can see, you know.

-But... I can't.

[light laughter] [animated conversations] VIVIEN: We are sort of an invisible group of women.

Film, in many ways, brought us together.

I am very grateful to all of you for being so freaking fun and nice and crazy.

-All the women that I met were just generous and fun-loving, worked hard, hard, hard.

It wasn't an easy job, but it was rewarding in the sense that you felt like you were part of a new family, you know?

[spirited melody on bass and drums] -Friday night, you know, close up shop, and there'd be a party.

And there was, everybody shared.

-That was so much fun.

And we would dance around, like, remember?

VIVIEN: Well, it always seemed like people should dance in the editing room, right?

-You guys were the best.

[super-lively music] VIVIEN: It's not just a job.

It's so much more than that.

[super-lively music continues, cheery conversations] This feeling of deep kinship.

-There was this kind of generosity of spirit among the sound people.

It was really just this opportunity to see how everything went down.

[super-lively music continues] [rolling chair squeals] -What are you doing?

-I'm cutting sound for Mosquito Coast .

There's Harrison Ford going back and forth.

VIVIEN: This huge group of people were working towards this one goal of bringing the story to life.

[music ends with a flourish] KAREN: Eventually, I met Vivien, and that is a story unto itself.

[simple, placid melody on piano] VIVIEN: One day, from across the room, this woman walked in.

After work, a bunch of us from the studio decided to go to Coppola's eccentric hamburger joint in North Beach.

[placid music fades into a bustling dinner] Karen played a tune on the jukebox.

[classic rock with a bright electric guitar solo] She climbed up on the countertop and started miming out the song.

♪ In the thrill of a knowing smile.... ♪ This was the craziest and most dynamic woman I had ever met.

♪ I stand here beholding my future unfolding ♪ ♪ right before my eyes [passionate electric guitar solo] ♪ my eyes!

We proceeded to have a film life together.

[metal sheet rumbles like thunder] [ The Right Stuff epic theme music] That started off a whole series of editing dialogue on more and more feature films.

[film whirring, cheerful, dulcet music] In preparing the tracks for the mix, I would work with the actor's words.

[dulcet music continues, blade scrapes tape] It was the most exacting work.

But I felt really close to the performance.

ACTOR: Roger.

And then when I got to do ADR and rerecord their voice, I would try to help the actor get back into the feeling of the scene.

SALIERI: How could I tell him what music meant to me?

[chorus begins Mozart's Requiem] VIVIEN: In '84, we worked on Amadeus .

Even though I was working in the dialogue department, Mozart's music would be emanating from the mix room and through the halls of the Saul Zaentz Center.

[chorus and orchestra build] I felt the same joy as I did as a child listening to the music in my family home.

[Mozart's Requiem : singers and orchestra crescendo] [ Requiem fades to gentle birdsong] [slow, rhythmic hand-drumming with chiming melody] In 1984, Karen and I bought a little farm on the wrong side of the tracks, and we called it Moms Head.

We began two different lives.

The fast-paced world of feature films on one hand and living on a two-and-a-half acre farm on the other.

[hand drums, chiming melody joined by cowbell] [music fades to birds, footsteps crunching on grass] [metal doors clatter and clank] When we first came here, the owner said, "Oh, there's a [bleep] kicker bar out there."

And we said, right.

[slow, percussive tune] When we got profiled by Bay Area Backroads , we had to change the name to the Buffalo Gals Saloon.

-I mean for very serious professional people... What's going on here?

-Well, why not?

[joyful but relaxed music, upbeat conversations] Make that Walter move.

VIVIEN: But every time we'd have a party, we'd have about three or four hundred people come over, and there'd be like something people couldn't bear to part with, but they thought, this is perfect for the [bleep] Kicker Bar.

And then it just slowly started accumulating.

[dissonant chords, pedals pumping] Anyway, it still works.

I have to get it cleaned so it doesn't play all the chords at once.

[wind rustles through plants] DR.

HIRSHFELD: I have many times talked to people who say, "I'm not that blind.

I'm fine.

I can get around the house.

I can see everything."

And I'll ask them, "What happens when you leave the place that you inhabit all the time and go someplace that you're not very familiar with?"

[tense, pulsing music] VIVIEN: Yeah, I went to LA for a screening, and I thought I'd be okay 'cause I had an assistant at the airport and a car to pick me up.

I went to the hotel, got in the elevator, and I couldn't figure out what floor I was on or how to get off.

And I didn't realize I needed a key card or anything about what was going on.

I said, I'm just stuck in this elevator, so I guess I'll just wait in this elevator until someone comes along.

And I just thought, how could you not have anticipated that?

And then so, I came right back home and signed up for Braille.

-Good for you.

-...with the pad of the fingers here.... [solemn music] We have this.... VIVIEN: I slowly, just for the first time the other day, just ran my fingers over it, and a word popped in.

And I just went, I'm touching a word!

[delighted laughs] I mean, because I've been using so much of my hearing that the sense of touch was this sense that I hadn't totally pursued.

And I just went, whoa.

It's coming alive in my fingers and going up to my brain.

It's a, it's a tough thing.

I'm up to E in the alphabet.

But you can make a lot of words with E.

[everyone laughs] And A through E, A through E. Just extraordinary that the word is touch.

[wind chime rings, deep, resonant tones] [distant birdsong] [dishes clink] One day I look out the window and there's a little man in a tree.

He kind of looked like Mark Twain in a way.

Right away when I saw it, it was only a day later that I had an appointment with my vision therapist.

And I said, "This little man showed up in a tree."

She goes, "That's the Charles Bonet syndrome."

People with sight loss often see children and animals and people in period costume, and they look completely real.

What I think caused it is the incredible eye strain that I had over about a week of trying really hard to write.

I don't wanna lose it due to eye strain, but... I can't give up this trying to see.

It's... I'm stuck.

I just don't wanna.... I wanna keep my sight as long as I can.

I just felt like I saw a bit of magic.

[tranquil music on piano] ♪ [tranquil music continues] ♪ [serene vocalizing layers over tranquil piano] ♪ I had this great run of dialogue editing and working on these fantastic films in the Bay Area.

But the work started to dry up, and I had to go to Los Angeles for a job.

['80s synth-pop] LA had a different vibe.

[drum machine, electric guitar fill out '80s synth-pop]s And they said, "Phone call for you," and it's Walter Murch.

And Walter Murch said, "We were wondering if you'd like to come back up to Berkeley and edit picture on Unbearable Lightness of Being."

And I went... [record scratch] "Can somebody make me a plane reservation this instant?!"

[a slow, sultry tango from the film] I had worked for decades as a dialogue and sound editor, and now to be a picture editor, it was an extraordinary opportunity.

-They were trying something different, searching for a new beauty.

-Yes.

We worked with some of the most wonderful men.

You know, I mean, they were so helpful.

So all the directors were really helpful in my career.

Phil Kaufman gave me one job after another.

-It does disappoint me that still to this day, there are, the statistics for women in roles of leadership in the different creative departments are no better than 40 years ago.

That sucks.

It's very complex to sort of tease it out.

Like, why didn't we get the opportunities we all deserved?

I mean, a lot of real, you look at the room and how much talent is sitting in a room.

And yes, we were successful in editing, but why was it so impossible to take that next step?

VIVIEN: And then there is this really strange space which is us as women, working our buns off, working on films reflected through the eyes of a man.

-As film editors, we're not always controlling, we're not controlling the content.

And we're artists for hire in a way.

So we're available for what's being made already.

VIVIEN: When I was first asked to work on Henry and June , I'd thought, holy cow, this is the beginning of cutting picture on big budget films.

And I just felt like, this is really success.

[orchestral music from the film plays] But my definition of success... started to change.

-This isn't me.

This is not me.

-Of course it's you.

It's the you inside me.

-It's a distortion.

[low, droning hum] VIVIEN: I remember thinking, you have to be really careful, Viv.

You could lose yourself.

[low, droning hum continues with night insects chirping] [low drone builds to an electric pulse] [bird chirps punctuating the low, droning hum] My eyesight's getting a little worse.

And my eyes are darting around looking for a way to put together the pieces.

[low, droning hum becomes a whisper] [solemn music] The Picasso face is turning into a blank face.

[solemn music, wet taps of the brush] And the blank face... [sighs] I can't really tell people's expression.

[no audible dialogue] [solemn music continues, no audible dialogue] Even though I'm kind of... tracking where their eyes might be and practicing that a lot, I still can't see their eyes, and I can't see the expressions on their face.

solemn chords slightly dissonant] I knew that they could see me, but I couldn't see them.

And I felt so naked, so vulnerable.

[solemn music continues, Karen's voice barely there] One of the things I really miss is like when Karen and I are just sitting in the living room watching TV or something and just glance over and just catch her eye.

But now I don't see her face.

And I just miss seeing my darling's face.

[sweet birdsong] [wind chime rings out as birds chirp] We're collecting stories about plants from history.

Sweet Woodruff was used during the May festivals and was May wine.

We have woad.

They mixed it up, and they painted their bodies blue in the old days in England.

So we have very ancient plants from history.

I took a break from editing feature films and immersed myself in growing medicinal herbs.

We knew nothing about plants when we first arrived.

Slowly, planting taught us.

The plants taught us.

KAREN: We work in the film business, which is very exhausting.

And so, we started doing this because, for our own health, it felt good.

The more we worked around these plants, the better we began to feel.

[bright, rosy music, distant children's voices] VIVIEN: And then children came.

Busloads of kids from local schools.

[music fills with emotion, happy children's voices] [rosy music pulses with life] Ever since relinquishing my daughter... I felt sort of awkward around kids.

And then one day, this young girl came up to me and took my hand.

And in that small gesture... I felt all of that awkwardness fade away.

[rosy music fills with optimism, brightness] Moms Head evolved from pasture grass to a medicinal garden to a forest.

[music grows pensive, birds singing near and far] [sweet, harmonizing vocals join pensive music] [music and birdsong continue] [music soars with emotion] [music fades, birdsong softens] PENFRIEND: Power on.

Start recording.

VIVIEN: Calendula officinalis.

PENFRIEND: Recording is done.

VIVIEN: (on recording) Calendula officinalis.

[delighted laugh] PENFRIEND: This is a new label.

Start recording.

VIVIEN: Withania somnifera.

[tender music] Ashwagandha.

PENFRIEND: Recording is done.

VIVIEN: (on recording) Withania somnifera ashwaganda.

[seeds sprinkle and rattle] [tender music continues] (on recording) Ashwaganda.

(whispering) Ashwaganda.

I know you.

Hmm.

[tender music continues] This'll be a little bit warmer for you.

[whirring, spinning, clacking softly] A switch to documentaries came as a crisis of conscience.

And then a chance meeting with documentary filmmaker Lourdes Portillo.

Lourdes, I'm here!

LOURDES: I'm gonna throw you the key, okay?

VIVIEN: Okay.

[poignant music, melodic and gentle] Hi, Honey-Bunny!

How are you, my sweetheart?

LOURDES: Old.

Old.

[both laugh] VIVIEN: You know, coming from feature films, and I had worked for all men in all of my film career up to there.

And then all of the sudden, I meet Lourdes Portillo, -The great cook.

-The great cook.

[Lourdes laughs] [playful march-like, percussive music] VIVIEN: You brought this kind of freedom.

Like, it expanded my idea of what was possible.

Te ha convertido en unpelele, una burla para todos.

¡Eso no es verdad, Mamá!

VIVIEN: And we both have a very sick sense of humor.

LOURDES: No, I don't.

[Vivien guffaws] [two slow chimes of a church bell] [two more slow chimes of the bell] Lourdes had this infectious and unique way of looking deeply into the world.

[families in the cemetery sing in Spanish] She imbued her films with a love of culture and family.

The stories that Lourdes told breathed life into me.

[group continues singing a ballad in Spanish] [singing in Spanish slowly fades] I just, I thought, this is really what I wanna do.

This is, it's heartfelt, it has meaning, and it just filled me with happiness.

Nothing in this earth has given me more pleasure, you know, than to be an artist who makes films.

VIVIEN: That was a major turning point for me in terms of leaving feature films and falling in love with documentaries.

[plaintive, dissonant music on piano] One of the most haunting films that Lourdes and I worked on was Señorita Extraviada , [plaintive music continues] about the disappearance and murder of hundreds of young women in Juarez, Mexico.

What we did to begin with was put their photographs up around near the ceiling of the editing room.

And we surrounded the room with their photos so that we were looking up as we worked.

They were descending down to talk to us from the heavens.

[a chorus sings with exquisite harmonies] [voices rise and fall, melancholy] LOURDES: There was so much horror that there was no handle for it.

There was no way to speak about it besides it being horror.

And you just wanna cry or you don't wanna see it.

And remember how we tried to figure out how we were going to approach it?

That conversation was so meaningful to me.

This film was going to be about the beauty of the girls that the mothers saw in their daughters.

[chorus continues, melancholy, angelic] We make an effort.

Yeah, we make an effort because we know what would happen if we don't.

[chorus slowly fades, mournful notes on piano] [silence] [bright chirps, chitters, and songs] VIVIEN: After counting down the years, my daughter turned 21, and I could finally start searching for her.

[lilting, but slightly tense music builds] But all the records were sealed or confidential, and everywhere I looked, I hit a brick wall.

And then my partner, Karen, helped me search for her.

KAREN: I took a little break from being an assistant sound editor, and I became a private detective.

One of the first things she told me when we started seeing each other seriously was that she had given up a child for adoption and that it was really hard for her.

I realized that the trauma alone made it impossible to search alone.

When she talked about resuming her search for her daughter, it was a no-brainer that I would, that I would help.

I went off to Sacramento where all the records for the State of California were kept.

On about the fourth day, I found a record for a baby girl born on the right day in the right location.

She lived in Redwood City.

I realized that she would've gone to high school there.

So I headed to Redwood City, to Sequoia High.

So, as I'm looking through the yearbook, I turn the page, and there's a picture of a young woman who looked so much like Vivien when she was a teenager.

I cleared my voice.

I went "ahem" and ripped the picture out of the yearbook.

[delighted chuckle] And drove right to the Saul Zaentz Company.

[music builds with anticipation] She's in her little editing room, and I take out the picture and I show it to her, and she instantly starts crying.

[music grows serene] [floorboard creak underfoot] [music fades] VIVIEN: My daughter and I first met in 1988 at a restaurant.

KATHLEEN: I was looking, you know, doing that, you know that when you're on, like, a blind date and you're like, you're trying to find this person, you don't really know what they look like.

[tender music] I think I saw you, and I'm like, oh, my God.

I think that's her.

So afraid.

And then you're sort of like, well, now I have to do this.

VIVIEN: You were stunning.

You walked in and I just went, oh, my God.

It was sweet and awkward at the same time, you know?

-Yeah.

-Lived in two different levels at the same time.

-I just remember feeling like I was holding my breath.

Everything was here.

Everything was here.

Just anxious.

[big sigh] VIVIEN: You were so gracious sharing photographs, you know, of yourself growing up.

And I looked at that book, and I thought, I get to see her grow up.

KATHLEEN: Oh.

I always knew I was adopted.

My parents always knew I was English and Irish 'cause that's what the documents said.

I was half Irish, half English, but mostly German.

[laughs] My German name is Kati.

My parents were immigrants from Germany.

I came around at four months, and then my brother came two and a half years later.

He's also adopted from a different family.

We lived in a huge house, acre of property in the middle of San Carlos.

It was a really beautiful place to grow up.

I was one of four of this family.

The adoption wasn't something that we discussed.

I was their child.

[pensive music] When I started coming up to Moms Head, I felt safe here.

So when things would go wrong, I found myself coming up here.

And I felt there was... I just could breathe.

VIVIEN: You just, like, walked in this place as if it had always known you, you know, and you had always somehow known this place.

KATHLEEN: I was excited, 'cause it was a door.

It was a little bit of light that was starting to come in, and there was some connection.

VIVIEN: When I introduced Kathleen to my family, my brothers and sister were shocked.

They never knew that I had had a child.

KATHLEEN: I always had this feeling like I think I'm supposed to be a part of a big family.

I just remember we were at some long table, and everybody was talking at the same time.

We all understood each other, and knew what you were saying.

[laughs] It felt more family-like.

[pensive music sweetens] VIVIEN: Each time I gave her a hug or held her hand, I just felt this was the feeling I longed for, for so many years.

We saw each other for birthdays and holidays, and we would talk on the phone for hours.

[sweet, pensive music continues] Ten years after finding Kathleen, I worked with Deanne Borshay Liem, who was adopted from Korea by an American family.

Our stories are vastly different, but I got a chance to just glimpse a little bit into the life of an adoptee.

DEANN: I think the fact that you had this experience with adoption just, it provided a deeper understanding of the story, and that brought out nuances that I think might not have been there if you hadn't been a birth mother interacting with this story, you know, as me, as an adoptee.

DEANN: (in the film) I tried to tell my mother that I wasn't who she thought I was.

I told her, "My Korean mother is alive."

I remember her taking me to the orphanage.

"We used to live in a house on top of a hill."

She said, "No, honey, that part's just a dream.

You're a war orphan, and both your parents are dead."

[somber music on bamboo flute] [bamboo flute echoes and stirs] VIVIEN: I would watch you like a hawk because I thought, you know, I need to know what Deann feels inside of her heart and how, and how you held this process of adoption.

You know, I think with adoption, there's always the question of what if.

What if I hadn't left?

What if I hadn't been adopted?

What if my mother had kept me?

What would I have turned out like?

[slow, harmonious chords on piano] VIVIEN: As I piece together my own life, I ask myself the same question.

What if I had run back to that room and grabbed my daughter?

If I hadn't signed the adoption papers?

If I had been able to bring her home?

[music continues, somber but sweet] [somber, sweet music continues] VIVIEN: The word mother, over the years, we've searched for kind of ways of what to call each other.

And so, I would email you as different names.

You know, let's try out this name this week.

Does this feel right for us?

You know, "Love, Bunny.

Love, Nena Bunny, Love, Vivien."

You were tiptoeing through the tulips on this word, knowing how much of a trigger word that was for me.

'Cause I didn't understand why I couldn't call you Mom.

-Mm-hmm.

-And I just, I still have a hard time with that.

-Right.

-It's that intimacy of mother.

-Well, I didn't bring you up, you know, so I didn't, I wasn't your first mother experience.

Now it's just like, Vivien, I love you for Vivien, okay?

Or I call you Bio-mom.

[both laugh] -I love it.

-I'm like, yeah, my Bio-mom.

-Yeah, yeah, I love it.

-So, "mother" is a trigger for my relationship with you as a mother... that puts my mom right next to you.

And those two can't sit in the same space.

So my mom was "Mutti."

So, there was authority in "mother," and... there's fear in that, and there's discomfort that, and there's... [big breath in] a lot of stuff in that.

[quietly haunting music, crows caw in the distance] VIVIEN: A little over a year ago, Kathleen started revealing more and more about her childhood.

[quietly haunting music continues] KATHLEEN: After my parents died, we were cleaning out the house, and we found all of my mom's diaries opened it up, and first thing I see is this comment about, "We adopted her.

She's four-and-a-half months old, she's got digestive problems, she's not eating well."

And, "oh, my God, this kid is so stubborn and petulant and I've gotta beat this out of her."

I just have a full-on breakdown.

Full-on.

And... it just, it came out, and I was grabbing.

I just was sitting there like this, just grabbing, and tears are coming down, and... it just, everything came out.

And all the sudden, this fit with this, and all of a sudden, oh, that's why I did this.

And oh, no wonder!

I was beat into submission.

I had no rights.

I had no voice.

I mean, we got beat with the belt, and my dad broke a door jamb because he went for my head.

I ducked.

You know, being tied up to the, to the fireplace because, you know, I would wander.

I didn't understand how my life connected through being born, being given up for adoption, being adopted, and then being abused.

[quietly haunting music continues] I was angry at you.

I was so angry.

It was the first time.

And I'm like, I can't talk to you.

I need to walk away from you and I can't talk to you, because this hurts too much, and I need to figure out who I am on my own.

[quietly haunting music continues] [music turns contemplative] VIVIEN: I felt responsible for what Kathleen went through.

I prayed I wouldn't lose her again.

[contemplative music continues] [contemplative music begins to brighten] KATHLEEN: I didn't know which way our relationship was gonna go.

VIVIEN: Right.

KATHLEEN: It had very little to do with you, but it started with you.

There was neglect and abandonment that wasn't addressed.

And then abuse and everything else was packed on top of that.

That wasn't you doing something wrong.

My parents did something wrong.

So, I needed to separate those two things out.

-Right.

It took a while.

It took almost a year.

-I couldn't run after you.

I just, I knew that what you needed was space.

It was a... an act of faith that you wouldn't leave and that you'd give me the time.

-Mm-hmm.

-And you did.

I'm making a conscious effort to be me, to allow you to see me.

And I have family.

I have real family now.

I know it's been 30 years, but I finally feel it because I can.

I couldn't before.

-Oh, my dear.

[contemplative music lifts, flutters] [music grows deeper, more spirited] [lyrical melody on piano over wide, gentle chords] VIVIEN: As much as I want to, I can't change the past.

When I was younger, I saw myself as someone who didn't really have a choice.

Now I wanna take responsibility... for the decisions I made.

[lyrical music continues, no audible dialogue] And that, in a way, frees me to be more present for Kathleen.

[Bluesy solo on piano, lilting and syncopated] [music continues over animated conversation] Losing my sight has allowed me to use my other senses, to drop in with people, to feel close to them, to feel people's presence a little more.

[joyful conversations, Blues piano rolls and dances] [cane tip glides, conversations, music continue] It's entirely possible... to hold the joy and the sadness in a moment.

To allow both to exist at the same time.

[music begins to slow and fade] And cut.

[click] [rough, deep scraping] [crinkly clacks] [buoyant, plucky music] [music continues, cane vibrates on stripes] [resonant thuds] [high-pitched, whirring slides] [clacking whirs] [creaking lever] [echoing metallic clang] [violin chords gently rising, over a springy beat] [music turns bouncy, cheerful, and bright] ♪ ♪ ♪ [Singers vocalizing] ♪ ♪

Video has Closed Captions

Preview: S27 Ep4 | 30s | An editor’s journey through vision loss and the power of reinvention. (30s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by: