Living St. Louis

October 20, 2025

Season 2025 Episode 21 | 28m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Great Rivers Greenway, Eagleton / Danforth, Cave-Ins and Sinkholes, I am St. Louis: Pearl Curran.

Twenty-five years of Great Rivers Greenway partnerships and collaborations, how two former U.S. senators from Missouri forged an unlikely but enduring friendship, the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District explains the difference between cave-ins and sinkholes, and I Am St. Louis: Pearl Curran, who rose to fame for claiming to channel a medieval spirit named Patience Worth through a Ouija board.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Living St. Louis is a local public television program presented by Nine PBS

Support for Living St. Louis is provided by the Betsy & Thomas Patterson Foundation.

Living St. Louis

October 20, 2025

Season 2025 Episode 21 | 28m 14sVideo has Closed Captions

Twenty-five years of Great Rivers Greenway partnerships and collaborations, how two former U.S. senators from Missouri forged an unlikely but enduring friendship, the Metropolitan St. Louis Sewer District explains the difference between cave-ins and sinkholes, and I Am St. Louis: Pearl Curran, who rose to fame for claiming to channel a medieval spirit named Patience Worth through a Ouija board.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Living St. Louis

Living St. Louis is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(upbeat music) - Welcome to "Living St.

Louis."

I'm Brooke Butler and, oh, hey, look, it's the arch!

No matter how many times we see it, we can't resist pointing it out.

This year marks the 60th anniversary of the completion of the tallest U.S.

monument.

And its symbolism ranges anywhere from perseverance and exploration to conquest and displacement.

But for St.

Louisans, it's home.

And in that spirit, we have more stories that give us that sense of connection.

From trails that transform our city to a friendship that defied politics from sinkholes opening beneath our feet to a St.

Louis housewife who claimed to write novels with a ghost, it's all next on "Living St.

Louis."

(lively music) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) - The Gateway Arch reminds us that St.

Louis was built at the confluence of rivers, roads, railways, and people.

For the last 25 years, Great Rivers Greenway has carried that same spirit, linking neighborhoods, parks, and even unlikely partners, creating trails that unite our region.

Brooke Butler has the story.

(playful music) - [Brooke] On September 15th, community members came together for The Great Gather Round.

This was Great Rivers Greenway's big celebration for their 25th anniversary and featured 1,500 feet of tables surrounding the Circle Drive of the Missouri History Museum, which is also one end of the St.

Vincent Greenway.

There were food trucks, activities, music, free cupcakes, but the real celebration is accomplishing 140-plus miles of greenway that connect the St.

Louis region, both physically and collaboratively.

- We have built with our community 140 miles of greenway trails where people can walk, run, ride a bike.

Give it up for your collective accomplishment of 140 miles and counting!

I don't know if y'all... - [Brooke] Great Rivers Greenway is a very unique system and model nationwide.

- It is.

To my knowledge, there's nothing else exactly like it.

- [Brooke] Emma Klues is the Vice President of Communications and Outreach for Great Rivers Greenway.

- To have 120 towns across three counties vote to create something that's a public agency to connect it all together, to our knowledge, does not exist anywhere else.

(bright music) - [Brooke] So let's go over that again, because one of the common misconceptions of Great Rivers Greenway is that it's a non-profit or an organization, and while they do have a foundation side of their work, they are a government agency funded by taxpayer dollars, voted into existence 25 years ago.

- I like the fact that we are building something that is going to be here long after I'm gone, that will be here for future generations.

- [Brooke] Todd Antoine is the chief of Planning and Projects at Great Rivers Greenway.

- When I started, I was employee number three at the time and hired by David Fisher, our first executive director.

It was David with his 30-plus years of running a major city park and trail system, me with my growing experience working at a regional agency, and then also Janet Wilding, who Janet was working at the time at St.

Louis County Economic Council.

So we all came in in the very beginning to really sort of taking our sort of government hats that we had and experience and putting the initial organization together.

- [Brooke] After consulting with numerous partners, agencies, and community members, they came up with what they called the River Ring Plan, consisting of 45 greenways across a 600-mile system.

- [Todd] And the whole idea was to set the vision.

And then in that, we started doing individual greenway plans.

So like our St.

Vincent Greenway was an early one, which is a very popular greenway from Forest Park up to UMSL.

- So I always tell people like, if you think you're at the Missouri History Museum and you're gonna go to the show at the Touhill, you're probably thinking about like three highways to get there.

- Right, yeah.

- There's the MetroLink, the Red Line.

So this greenway parallels the Red Line, so you can kind of hop on and off as you need to, going all the way up to the North Hanley Station.

- But you would never know the MetroLink was there.

I mean, this feels like you're in the middle of nature.

- [Emma] Yes.

- [Brooke] And that is one of the goals, right?

Is to have people feel more connected with nature, but in the city.

- Absolutely, in the whole region.

So we want people to have access to natural spaces, access to transportation choices, and whatever they need for them to live healthy, active, vibrant lives.

- [Brooke] But it's not just Great Rivers Greenway guessing or assuming what the region wants out of these trails.

Each project involves multiple partners, communities, and various opportunities for the public to give feedback.

- Community engagement is critical to our work.

It is the foundation of how we are successful because there's a responsibility as being good stewards of our tax dollars for us to be gaining trust and working with residents, working with folks in the communities about a potential project.

And so projects always have in the very beginning, you know, there's always the fear of crime about, oh, who's gonna be out there on these greenways and things like that.

But once we really got the system built and started building sections all over the three counties, and people start to say, "Oh, now I see what that looks like, and this is great, and I have a great experience on it and things."

It's building trust and understanding, and I feel now that we've been around for 25 years, there are people that are like, "When's it our turn to get a..." They want, you know, they want the trail that's identified on the map as the coming soon at some point.

- [Brooke] And one of those projects coming soon is the Baltic Creek Greenway in St.

Charles County.

We attended one of the last public forums for the project where you can see the adaptations to the plan based on community feedback.

- That kind of feedback and the feedback that we hope to get tonight can be very valuable for us to... - What I always appreciate, and we hear this a lot from residents and people on those on the committees that we talked about, or people that just go to our public meetings and whatnot, that comments that they made or things that they saw and the conceptual thing.

Like, they're like, "Oh, I see what I said back then."

You know, may have been a year and a half ago.

"I see it's actually been built and being constructed."

People love seeing that.

- [Brooke] Sometimes you're working with, I mean like just mile to mile, it's different municipalities.

- It might be tenth of a mile.

- Yeah.

- Sometimes we'll build a greenway that's maybe three miles and there might be four different towns and they may or may not know each other yet or have been collaborating.

And so the process of building the greenway really does connect the region together, even just by way of talking about it.

The day-to-day operations and maintenance is for the partner to handle.

So whether that's, you know, a county park system or a municipality, then they are the ones that might be like patching, you know, a hole in the pavement or fixing a bench or things like that.

But we know that with 120 towns in our region, they're not all the same.

They don't have all the same resources.

So we really try to jump in and help with our own staff, with vendors, with volunteers, with, you know, trainings for our partners.

Maybe they've not taken care of a rain garden before.

They don't have something like that in their community.

So whatever it takes, we want everyone, we think everyone deserves great greenways, so we wanna make sure that we jump in and help however we can to have a great system across 1,200 square miles.

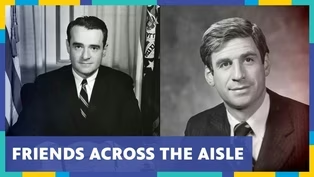

(uplifting music) - The Thomas F. Eagleton Courthouse became a part of the St.

Louis skyline in the year 2000.

And the namesake of this towering building is a key player in our next story.

In today's political climate, it can sometimes seem like Republicans and Democrats will never get along.

But there was a time in the not too distant past when two senators, one Republican and one Democrat, didn't just work well together, but were actually friends.

- Right now, you look at, just look at pictures of people today active in politics, they all look mean.

And it was the opposite of that, there was absolutely none of that.

- [Veronica] That's former Republican senator from Missouri, John Danforth.

From 1976 to '87, Danforth had a close working relationship and a friendship with his senior senator, Thomas Eagleton.

Despite their differing political beliefs, the two actually had a lot in common.

The State Historical Society in Columbia, Missouri, currently has an exhibit about their relationship, which is open until the end of the year.

But before we talk about them together, let me introduce them individually.

Thomas Eagleton was born in 1929.

- He was born into a family that was pretty well connected in St.

Louis, not perhaps as well as Danforth, but still very well connected.

He attends Country Day School in St.

Louis.

- [Veronica] Sean Rost is the assistant director for research at the State Historical Society.

He says Eagleton experienced a quick rise through Missouri politics, becoming St.

Louis Circuit Attorney in 1956, and Missouri Attorney General in 1960.

- I met Thomas Eagleton when he was the Attorney General.

It was probably late '61 or '62.

- [Veronica] That's U.S.

District Senior Judge Edward Filippine.

He was appointed by President Jimmy Carter.

At 95 years old, he's currently inactive.

In 1964, Eagleton asked Filippine to run his campaign for Missouri Lieutenant Governor.

- And that came as a shock to me because this was a statewide campaign.

I had done some work in townships and county, but never really participated in a statewide campaign.

That was the start of our long political relationship and our lifelong friendship.

- [Veronica] In 1968, Thomas Eagleton ran for U.S.

Senate for the first time.

- [Sean] Eagleton essentially pushes aside the incumbent, Edward V. Long.

He wins, and then he wins a very narrow election against Tom Curtis, who was a Republican from St.

Louis as well.

He's being suggested as a possible running mate for George McGovern in that election of 1972.

- [Veronica] And though Eagleton wasn't McGovern's first choice, he was picked as his running mate on July 14th, 1972.

- So there was a lot of support for that.

Eagleton was seen as being a very popular senator.

- [Veronica] But his vice presidential run was short-lived.

- Due to controversies and questions about his mental health and prior treatments for depression, and particularly shock therapy in the 1950s and '60s, there was a stigma attached to that.

And so McGovern's backers were kind of pushing him to drop Eagleton from the ticket, which he ultimately convinced Eagleton to do.

- [Veronica] His candidacy lasted about 18 days.

The exact source who leaked the information is still unknown.

- [Sean] He felt he had gotten past it, and that was where he was kind of standing on the issue, was that he didn't feel like he needed to disclose it because it was not something that was presently afflicting him, in his mind.

- [Veronica] John Danforth didn't know Eagleton well at that time, but he says most of the people in Missouri fully supported Eagleton during the ordeal.

- I mean, the reaction in our state was highly favorable to Tom Eagleton.

I mean, he was viewed as sort of the champion of the people during that.

It's not, it's a terrible thing to see somebody go through something like that.

- [Veronica] But besides being dropped from the presidential ticket, Eagleton's career wasn't really hurt by the controversy.

In fact, he remained a U.S.

Senator for 15 years, and in 1974, he was joined by John Danforth.

- [Sean] And he comes from a very prestigious family.

He is the grandson of the founder of Ralston Purina in the city of St.

Louis.

- When I was about 10 years old, our parents took my brother Don and me to Washington to see the sights.

And we sat in the Senate Gallery and I looked down and I said to myself, "I'd like to do that someday."

And I also remember verbatim what my dad said as we were filing out of the Senate Gallery, which was, "What a bunch of windbags."

So that's from a very early age, I was interested in politics.

- [Veronica] In 1968, Danforth was elected as Missouri's Attorney General, the first Republican to hold that office in 40 years.

- But he's attributed in a lot of ways of starting a Republican revival in the state of Missouri.

Almost immediately afterwards, his office of Attorney General becomes the launching point of many different careers.

- [Veronica] Danforth first met Eagleton that same year.

- He reached out to me and said, "You know, would you like to visit about the AG's office?"

Which I did.

And he told me about it, what it was like in his day and some of the people who were still in the office and his views of how they were and what they were doing.

- [Veronica] Danforth was sworn in to the U.S.

Senate in 1977.

After the ceremony, he and his family got together for dinner and invited his fellow Senator, Thomas Eagleton, and his wife, Barbara.

- I do remember that during that dinner, Tom turned to me and said, "I know you wish your father was still alive."

What that said to me is, "I see you as a person."

You know, "I see you as a person whose father died just a few years ago.

My father died, and that's how I see you, not as a senator, but I see you as a human being."

And that set the tone for our relationship, which existed throughout our time in the Senate together, and in fact, until the day of his death.

His views were different than mine, but it was so much fun.

You know, really, when politics works, it should be fun and there should be humor in it.

He was a very funny man.

- Jack Danforth's family was Purina, and they had Dog Chow.

And so he had seen an ad for Dog Chow.

So he wrote Jack, "Dear Jack," scribbled this note, "I just saw an ad for Dog Chow, and they said it's good for the dog's hips.

Now, my dog, Pumpkin Eagleton, has been taking Dog Chow for a long time.

Her hips are just wonderful.

In fact, they're so good, I started to take it myself."

- There were folders that were nothing but barbs going back and forth between Danforth and Eagleton, you know, just ribbing each other about something.

So we wanted to do a whole panel just on that.

- [Veronica] Laura Jolly is the assistant director for manuscripts at the State Historical Society.

She read me one of the notes Eagleton wrote to Danforth about the junior senator's vote to ratify the Panama Canal Treaty in '78.

- You know, this is just typical Eagleton.

"Danforth, will you please stop voting the way you do?

I simply followed your lead on Panama, and look at the trouble you've gotten me into."

(laughs) - [Veronica] The treaty would give the canal to Panama by the year 2000.

- Early in the process, I announced I'm gonna vote for the treaties.

He thought that was so funny.

And he was, so he, he called me for a while, Panama Jack.

That was what he called me.

- [Veronica] But they took their political relationship seriously.

And though they often voted differently, one thing they did agree on was the welfare of Missouri.

- They were always willing to keep their door open for one another to kind of have that conversation about what's in the best interest for Missourians, but also how do we feel it when we address it through our conscience as well.

The Meramec Basin Project was one of the initial ones where they were split, and then Danforth and Eagleton came together to decide the idea of a referendum.

They supported the idea of keeping the St.

Louis Airport in the city of St.

Louis, or I guess I should say, in the county of St.

Louis.

- [Veronica] They often agreed on conservation in Missouri.

Both supported creating a preserve called the Irish Wilderness in Oregon County.

- Another one, a big one, is gonna be kind of updating the lock system on the Mississippi River.

They were both in support of updating those lock systems and addressing that as well.

I think in a lot of ways, you know, the legacy of them is not just simply built in concrete, you know, the locks and dams on the Mississippi River or even the Eagleton Courthouse.

But you know, the legacy of that bipartisanship, you know, really influenced Missouri politics going forward.

I think in a lot of ways is, you know, we could think about so many political leaders of more recent eras who served as campaign staff or aides to both of them, you know, or either of them, who put them on a course to impact Missouri politics later on.

- [Veronica] Eagleton retired from politics in 1987, but the two remained close.

- You know, we were Cardinals fans.

We'd go to the ballpark together.

He called Beffa's, which is a restaurant on Olive, I guess, and he called it his club.

So we'd go to have lunch at Beffa's and just chat and about whatever and about politics and, oh, disagreement.

- [Veronica] While Danforth remained a Senator, Eagleton became a professor at Washington University and advocated for bringing the Rams NFL team to St.

Louis.

In 1994, both Eagleton and Danforth were named Men of the Year by the "St.

Louis Post-Dispatch."

The first time two people were ever chosen for the award.

And in the year 2000, St.

Louis's skyline would change in the name of Thomas Eagleton.

In the early nineties, a plan began to build a new courthouse downtown.

Senator Kit Bond reached out to Judge Filippine about the proposal.

- He said, "I want to name the building.

I wanna put a bill in for Tom Eagleton."

And that's how the bill went in, and it just went straight through.

No problem.

- [Veronica] Eagleton, Danforth, and others broke ground on the building in 1994, and it was completed in 2000.

- But that word came back to me that he had talked to some people and see if there was a possibility of a little change.

The bill was already done, and they told him no.

"What do you want to change?"

He said, "I would rather if it was named the Eagleton-Danforth United States Courthouse."

That's how close they had become.

- [Veronica] On March 4th, 2007, Thomas Eagleton died at age 77.

At his memorial service, Danforth delivered a eulogy for his friend, describing what he thinks heaven would be like for Eagleton.

- I imagine a glorified Beffa's.

(members laughing) And Tom is in the middle of things, and all of us are gathered around him, and he's holding forth, as always, giving us his opinions on politics and baseball.

And God willing, I'm there too, present at the banquet, taking in all Tom's words, disagreeing with half of what he says, just as I always did, and loving every bit of it.

That for me would be heaven.

- [Veronica] Danforth hopes everyone, not just other politicians, can learn from their friendship.

- And we see right now that politics breaks up families.

It's the Thanksgiving dinner thing, you know, and people lose friendships.

They all, because they're arguing about politics.

It can't be that way.

We can't let politics do that to us.

So we've gotta be able to conduct politics in a way that's within the structure of friendships.

- St.

Louisans bond over the good, bad, and ugly, like potholes, most people have had run-ins with these, probably literally.

Our next story is not exactly about those notorious tire traps, because below the surface to see what could be causing other road hazards we've been seeing more of recently.

(intriguing music) For the past several months, St.

Louis has experienced multiple large cave-ins: the one at Pappy's Smokehouse, the one at Cass and 17th, and the one on Park Avenue.

This is not a new issue, but it begs the question, why do St.

Louis's streets keep collapsing?

To understand cave-ins and why they happen, you first have to know what's unique under St.

Louis, and that is our city sewage system.

It's old like many systems in larger cities.

It's 10,000 miles of pipes, and it's a complicated system.

Jay Hoskins with the Metropolitan Sewer District says when we talk about cave-ins, you have to look at how our system is set up.

- So the older part of St.

Louis, normally we think of St.

Louis City, but also portions of St.

Louis County, is what we call a combined sewer system.

So you have much larger diameter sewers.

I think I call, tell my kids, this is the "Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles" sewer.

So those are the big sewers where the turtles might have lived, okay?

Then that sewer pipe is large because it has to convey both the stormwater and the sanitary flow or the wastewater flow in the same pipe.

And so when it's a day when you don't have any rainfall, when the sun's shining, you have very little flow in that pipe.

But when it rains, those pipes get very, very full.

And that combined sewer system is something that's, as folks developed west, and they went out into other parts of St.

Louis County, folks said, "That's just not state-of-the-art anymore.

That's just not the way we want to go about building sewers anymore."

So they built two pipes.

They built a wastewater-only pipe and a stormwater-only pipe.

- [Olivia] According to the EPA, only around 700 communities in the U.S.

have combined sewer systems, most of them in the northeast region.

That combined system, environmental conditions, and our status as a river city impact our overall system.

We also have karst terrain, a landscape supported by eroded limestone, creating ridges, sinkholes, and other characteristic landforms.

- But those natural formations are really important to the region's geology.

When we think about all those things going on at the same time, the complex nature of our sewer pipes and the complex nature of our geology and the way that those sewer pipes work in that geology, it makes operating our sewer system very complicated.

- [Olivia] Unlike sinkholes that come from our natural environment, cave-ins come from our constructed or built environment.

So let's say something like sewage pipes faulting, redevelopment, construction changing the environment, pretty much anything that lets water go where it wasn't before can create that void underground.

Most of the time these cave-ins open up, it ends up under MSD's jurisdiction.

They're inspecting around 30,000 manholes and 300 miles of our wastewater system annually, trying to catch these cave-ins before they become a nuisance or a safety hazard.

But there's still a level of fear that can arise when people see the streets they drive, walk on, open up.

And in a city of potholes, it can be hard to tell what needs attention and what doesn't.

- If you see something, say something.

If you think that the street is collapsing near an inlet where the water would normally go, or out in front of your home where you think your sewer lateral goes through, we want to know about it.

It's not gonna help us if you put it on social media.

It doesn't help us if you put it on TikTok.

You need to call us: 314-768-6260.

That will trigger a series of motions by MSD staff to go and investigate and determine if there's something that needs to happen.

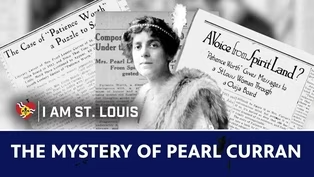

- I'm Veronica Mohesky, and today I'm here with Dr.

Jody Sowell, president of the Missouri Historical Society, and for this week's "I Am St.

Louis" series, our story's a little bit spookier.

- So if St.

Louis could introduce itself, it would say, "I am the place where a dead English woman wrote bestselling novels."

That woman is Pearl Curran.

Actually, it's Patience Worth.

We'll get to that in just a second.

Pearl Curran was an author here in St.

Louis, and starting in 1913, she wrote an amazing amount, seven novels, countless plays and poems and short stories, and her work was celebrated.

"The New York Times" said her first novel was a feat of literary composition, but what she said is, "I'm not writing these things.

They're in fact being written by a woman who lived in the 1600s named Patience Worth, who I communicate with through a Ouija board."

It was a big hit in St.

Louis.

People would actually go to her house to see her work the Ouija board and talk to Patience Worth.

An amazing and fascinating, a little spooky chapter in St.

Louis history.

- Absolutely.

Why is Pearl Curran somebody we're still talking about today?

- You know, I think that oftentimes these artists get lost to time.

I mean, this was a person, however she actually wrote the novels, who was celebrated in her day, was celebrated by authors of the time.

And so we deserve to know these people, and if you want to read her work, you can still find it at the Missouri Historical Society.

- That's really cool.

(upbeat music) - And that's "Living St.

Louis."

But hey, I have a question.

When people come visit you from out of town, do you bring them to the arch, or where are those go-to places that you bring people around St.

Louis?

Let us know at ninepbs.org/lsl, and the "Living St.

Louis" team might visit there next.

And don't forget, you can catch all these stories and more on Nine PBS's YouTube channel or the PBS App.

I'm Brooke Butler.

Thanks for joining us.

(lively music) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) (lively music continues) - [Announcer] "Living St.

Louis" is funded in part by the Betsy & Thomas Patterson Foundation and the members of Nine PBS.

Great Rivers Greenway Celebrates 25 Years of Connecting St. Louis Through Trails

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2025 Ep21 | 6m 28s | Marking 25 years of Great Rivers Greenway. (6m 28s)

How Senators John Danforth and Thomas Eagleton Worked Across Party Lines

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2025 Ep21 | 12m 43s | Former Missouri senators Thomas Eagleton and John Danforth forged an enduring friendship. (12m 43s)

The Place Where a Dead Englishwoman Wrote Best-Selling Novels | I Am St. Louis

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2025 Ep21 | 1m 35s | Pearl Curran gained national fame for her claims of channeling a medieval spirit. (1m 35s)

Why are Cave-Ins and Sinkholes Popping Up in St. Louis?

Video has Closed Captions

Clip: S2025 Ep21 | 3m 59s | St. Louis has experienced several sinkholes over the past few months. (3m 59s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipSupport for PBS provided by:

Living St. Louis is a local public television program presented by Nine PBS

Support for Living St. Louis is provided by the Betsy & Thomas Patterson Foundation.